A few weeks ago, we published an article that characterized Gilead as a “Value Trap.” That article was a follow-up to an earlier article which used our work on Gilead as an example of how a solid conceptual framework could help investors make better decisions. We caught a lot of flack for the recent characterization of Gilead as a value trap, but our opinion was redeemed on February 7th, when the stock fell heavily after a disappointing earnings announcement.

In today’s article, we’ll take another look at the valuation process – the most important weapon in an investor’s arsenal – in a continuation of the Gilead example. We would invite new readers to read through each of the earlier articles as well, to get a picture of the overall process!

Investing Anecdotes are Dangerous!

What interested us in September 2016, when we made our original analysis of Gilead, was the noise among the value investing community about what a deal Gilead was because the stock was trading at such a low Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio (See our article Three Things You Should Know About Gilead).

Figure 1.

We believe that P/E ratios, analyst opinions, chart patterns, and all of what on-air pundits say are all forms of investing anecdotes – dangerous fairy tales that substitute for true understanding of company’s business and an investment. Investing anecdotes are often pithy and can seem sensible, but they can get an investor in a lot of trouble if relied upon as a basis for investing decisions.

Instead of placing stock in anecdotes, we suggest a repeatable, disciplined, cash-based model for understanding the company in which you are investing your hard-earned capital:

- Understand the Golden Rule of Valuation.

- Understand what factors drive value at a company.

- Have a testable hypothesis for each value driver that you can observe.

- Focus on operational performance rather than stock price as a measure of success.

From there, one can use the company value knowledge they have diligently compiled to make investments that repeatedly capitalize on the difference between market price and that value.

Gilead’s Value Trap Characteristics Were in Plain Sight

Heading into the fourth quarter last year, a number of articles had been written about how the Gilead was historically undervalued on the basis of its P/E ratio (= current market price / share divided by earnings per share). However, ratio analysis has a material flaw in that it implies assumptions about future cash flows that the user does not always think about or for which they do not account in their analysis (See our article entitled The Vampire Squid Versus The Sun to find out why).

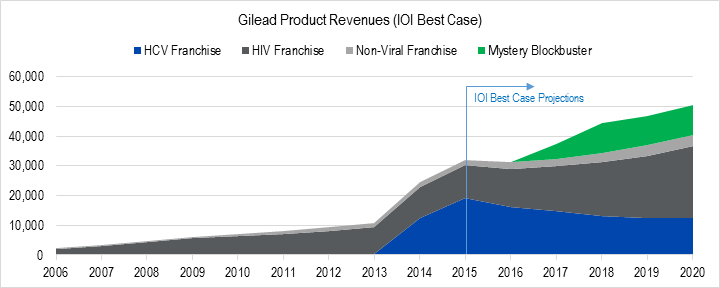

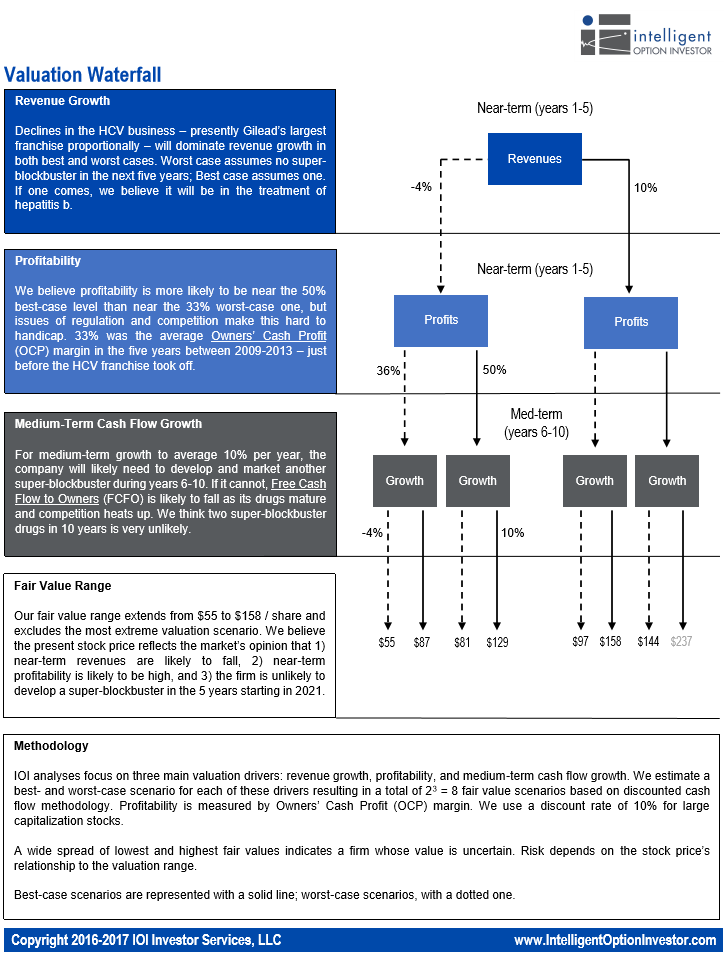

IOI’s study of Gilead led us to conclude that there were serious risks to the Company’s revenue projections due to a falloff in demand for their blockbuster Hepatitis C treatments (HCV). The pace and magnitude of declines in that core business led to operating scenarios where GILD’s low P/E ratio was more than justified.

While we could generate business scenarios that earned valuations above September 2016’s share price in the $80 range, it was the uncertainty, or the wide range of possible values, that gave us pause. We did not know exactly what would happen, but we knew that the uncertainties around Gilead’s HCV franchise generated more downside risk than upside potential, despite the currently low PE.

Figure 2. Source: Company Statements, IOI ChartBook on Gilead (9/27/2016). Note that even in this best-case scenario, we thought Gilead’s HCV franchise would be much smaller than the HIV franchise in 2020.

To note, Gilead’s share price was low relative to 2015 earnings and low relative to sell side analysts projected 2016 earnings, but it does not appear so low if the earnings fall through the floor suddenly. That “fixes” your PE ratio in a very unhelpful way. It is the textbook definition of a value trap: the PE is low not because the P is low, but because the E is unsustainably high.

The HCV Numbers Were Startling

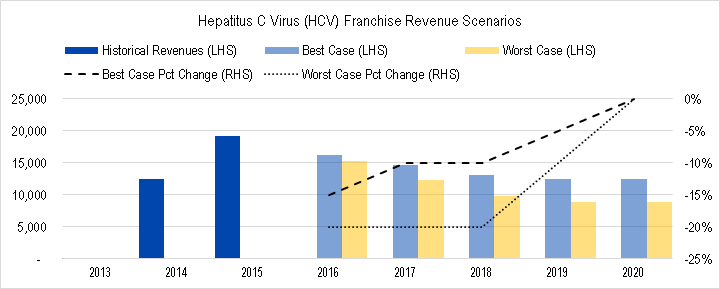

In 2016, Gilead’s global revenue was down roughly 7%, driven by a 22% drop in the HCV franchise. This is actually very close to our worst-case assumptions for 2016’s HCV revenues of 20% (For more revenues detail see Making Sense of Gilead’s Revenue Stream), so looking at those numbers, we were satisfied that we had understood the company’s revenue stream pretty well.

However, we were taken aback by Gilead management’s guidance for HCV revenues in 2017: a range between $7.5 billion and $9 billion. IOI’s worst case HCV revenues for 2017 were over $12 billion – implying another annual 20% drop. Gilead’s guidance implies a drop of 35% in the best case and 50% in the worst case!

Figure 3. Source: Company Statements, IOI ChartBook on Gilead (9/27/2016). Our 2016 HCV revenue forecasts were close to actual values. However, Gilead’s guidance for 2017 segment revenues are even lower than our 2020 forecasts.

What We Learned

Our worst-case HCV scenario assumed that the size of the HCV market would stay essentially the same and that Gilead would hold onto its strong market share position, but that the only way it would stave off competition is by discounting prices by more than 50% over the next five years. Another way of stating this assumption is that it would take five years for the revenue potential of the market to drop in half.

The company announcement suggested that the market potential might drop in half over a single year. Clearly, our assumptions about the patient population were too optimistic, even in our worst-case scenario. We will go back to the drawing board and incorporate this new information into our model, then next year, see if we are correct with our new assumption.

On the bright side, we also learned that our caution in the name was warranted, and that – as we suspected – the company had much more of what we call “valuation risk” (i.e., the risk that the value of the company is lower than the present stock price) than most people assumed.

Intelligent investing is the process of shunning investments with valuation risk in favor of creatively investing in companies with “market risk” (i.e., the risk that the price of a stock may diverge from its intrinsic value).

Trust the Process

This is not about having an “investing system”. By avoiding the anecdotes and developing a sensible, demand-based hypothesis about Gilead’s business, we were able to avoid a significant loss of capital.

It is not impossible for individual investors to become excellent investors with strong analytical skills, but they must have a disciplined, repeatable process.

Our next step? We will update our valuation model and see how our greater certainty around the HCV franchise impacts the Company’s value. Can Gilead work its way out of the value trap? Stay tuned!

Figure 4. Gilead Valuation Waterfall. Source: IOI Analysis

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com