In this series of articles, we’ve taken a look at Union Pacific’s revenue growth and at its investment spending (one, two, three, four). The last short-term value driver at which to focus in on is profitability.

While we touched on profitability on an Owners’ Cash Profit (OCP) basis in our article on UNP’s maintenance capex, this article looks at the factors driving Union Pacific’s operating profit increases over the last fourteen years, then triangulates operating profits with OCP.

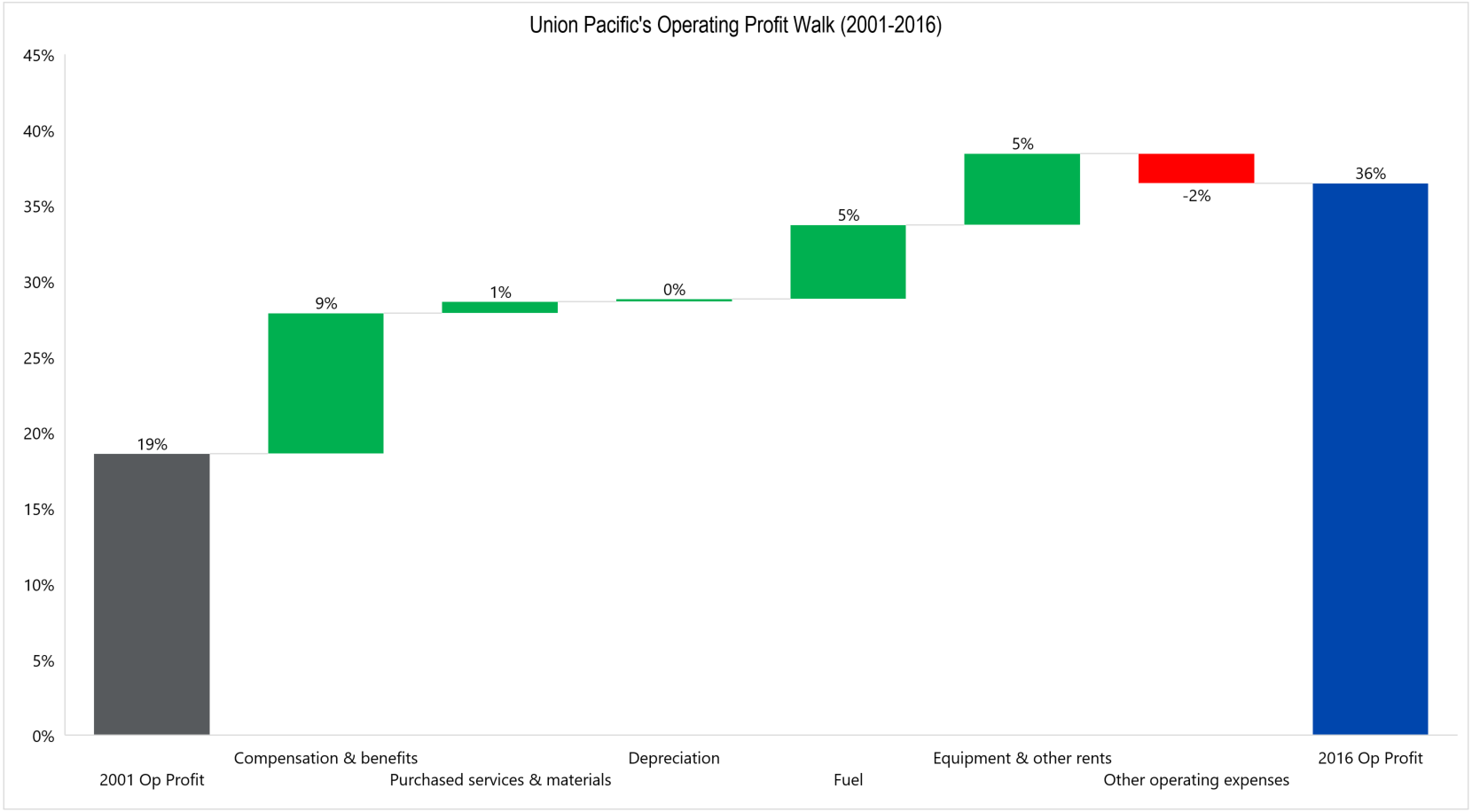

Union Pacific generated an operating profit (earnings before interest and taxes) margin of 19% in 2001; this measure had increased to 36% in 2016 — representing a truly phenomenal increase of 17 percentage points. Looking at the root cause behind this increase from the perspective of each operating expense category, we find the following.

Figure 1. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis. In this chart, if the company spent less as a proportion of revenues on an item (e.g., Compensation & benefits) in 2016 versus 2011, the percentage improvement is shown by a green column. Other operating expenses increased as a proportion of 2016 revenues compared to 2001 revenues, so is shown in red – the proportional increase in these costs decreased operating profits.

A proportional reduction in Compensation and benefits expenses contributed the most to Union Pacific’s margin increase. Fuel and Equipment-related expenses add another 10 percentage points of margin increase. Of these, equipment-related expenses have been discussed already (see figure 4 in this article), so this article will focus on how spending on Compensation and Fuel has affected Union Pacific’s profitability

Compensation and Benefits

During the 2001-2016 period, revenues per employee grew by an average of 5% per year while average compensation expense per employee grew by only 3% per year and the total number of employees dropped. This dynamic — revenues growing more quickly than costs and the number of employees dropping — is responsible for the nine percentage points of margin increase shown in figure 1 above.

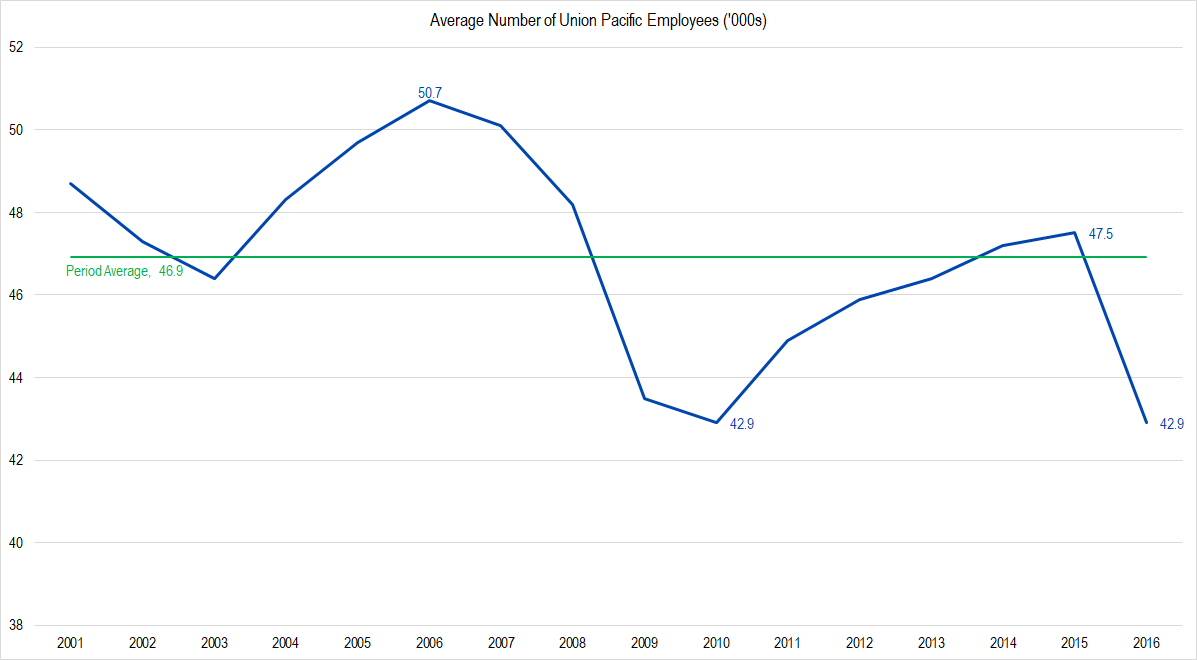

Looking at the number of employees shows that the drop in employment has not been uniform.

Figure 2. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

For the first nine months of 2017, the numbers of employees has only dropped by around 700, indicating that the drastic fall off in employee count has slowed. The drastic fall-offs in 2009 and 2016 are in large part facilitated by temporary lay-offs called furloughs. The furlough system allows railroads increased flexibility in labor costs in return for paying a portion of each employee’s salary into a pool to compensate out-of-work railroad employees.

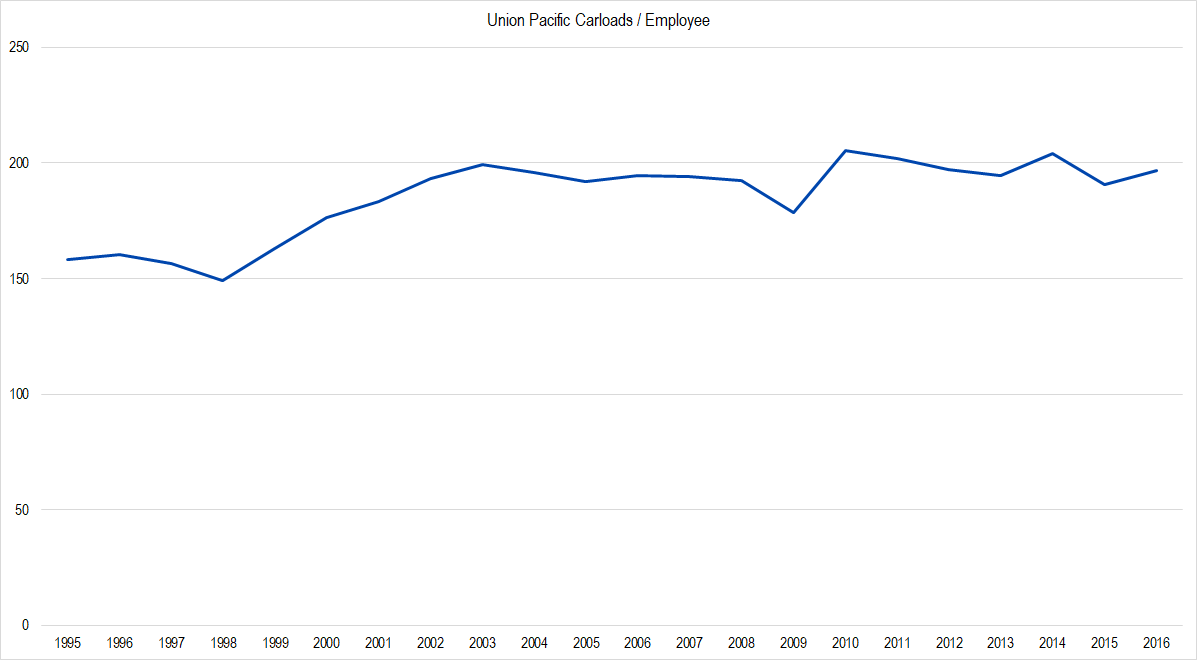

To judge the degree to which the drop in employee numbers is a sign of increased efficiency, we compared the carloads transported to the number of employees.

Figure 3. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

Efficiency clearly improved during the 1995 – 2003 time frame, but has since flattened out at about 200 carloads transported for every one employee. The fact that Compensation & benefits as a proportion of revenues has fallen from around 35% in 2003 to between 20% and 25% over the past few years coupled with the flat-lining of carloads per employee implies that a great deal of Union Pacific’s wage-related profitability increase is due to higher pricing rather than greater operational efficiency.

This observation underscores the importance of Union Pacific’s continued pricing power to its profitability increases. On the basis of the data shown here, we do not believe that there is room for increased profitability due to efficiency increases.

Fuel

Fuel is a major expense for a railroad. Each diesel locomotive holds around 4,900 gallons in its tank, so topping the tank for the entire fleet of 8,200 locomotives gets pricey.

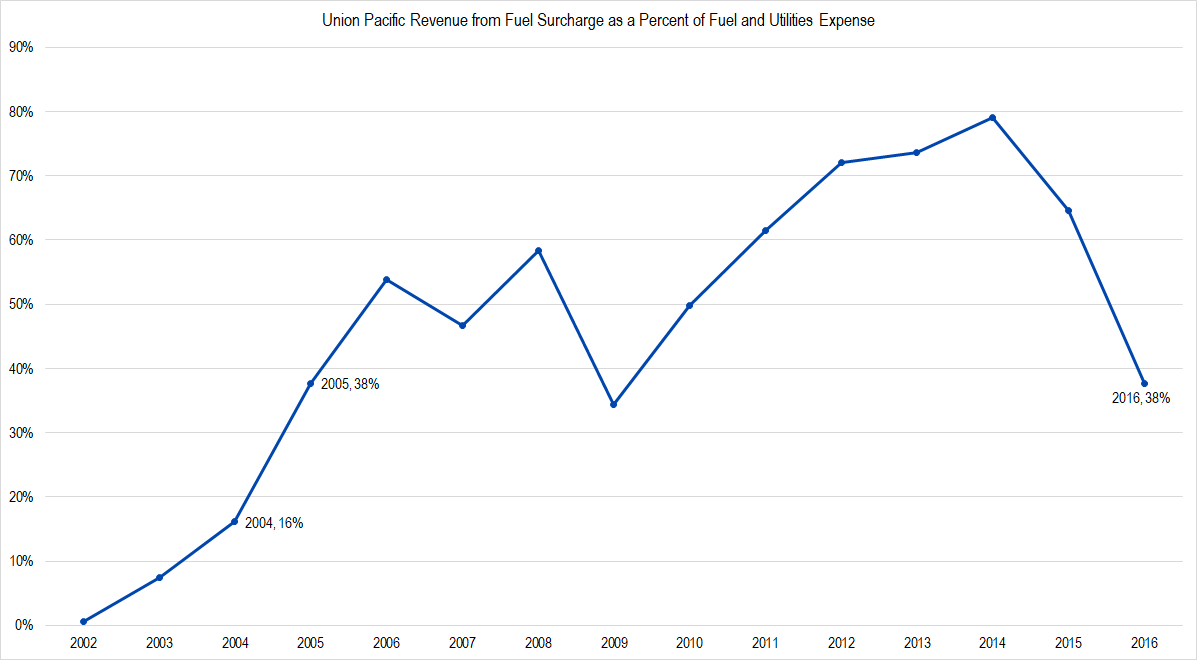

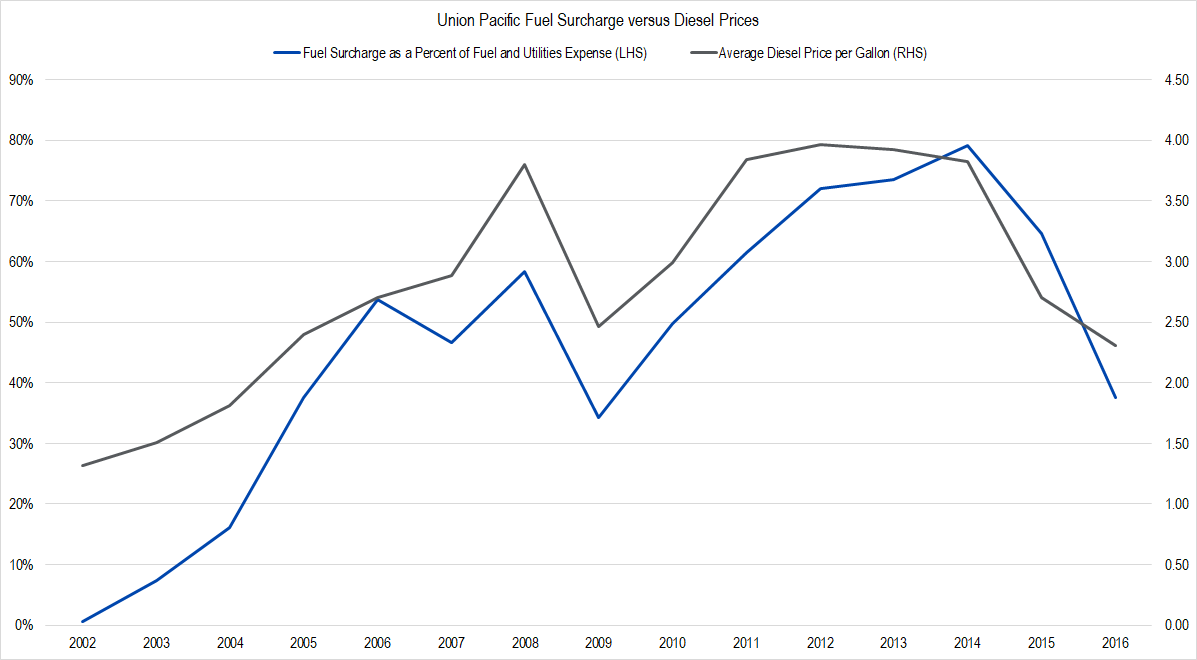

However, as mentioned in our article analyzing Union Pacific’s revenues, railroads pass part of the cost of fuel through to their shipper customers in the form of fuel surcharges. Fuel surcharges have been used by the railroad industry for a long time — we’ve found reference to them as far back as in the 1970s. However, shippers did not start to complain to the Surface Transportation Board about how rails applied the surcharges until circa 2005. One look at the chart below offers some clue as to why.

Figure 4. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis.

Unfortunately, the company does not provide fuel surcharge data for 2001, but assuming it was somewhere in the range of 2002-2003, the amount of fuel costs that shippers were subsidizing on behalf of Union Pacific’s shareholders saw an enormous jump starting in 2005, especially.

The amount of the surcharge subsidy follows the average price of diesel fuel.

Figure 5. Source: Company Statements, Energy Information Agency, Framework Investing Analysis. Note that the diesel price listed above is the average retail not wholesale price. Railroads certainly pay the wholesale price, but wholesale and retail prices should be tightly correlated.

Put simply, when diesel prices are high, shippers tend to provide a very large subsidy to railroads and when they are low, the subsidy drops. While I was able to find reference to fuel hedges in Union Pacific’s older financial statements, the 2016 annual report makes no mention of it. It seems like shippers are unaware that they are providing free call options on the price of diesel fuel to the railroads. We believe that this dynamic is at the root of the five percentage points of profitability increases related to fuel.

Now that we understand the dynamics of Union Pacific’s profitability increase, let’s look at what the company is guiding and triangulate that with our OCP forecasts.

Company Guidance

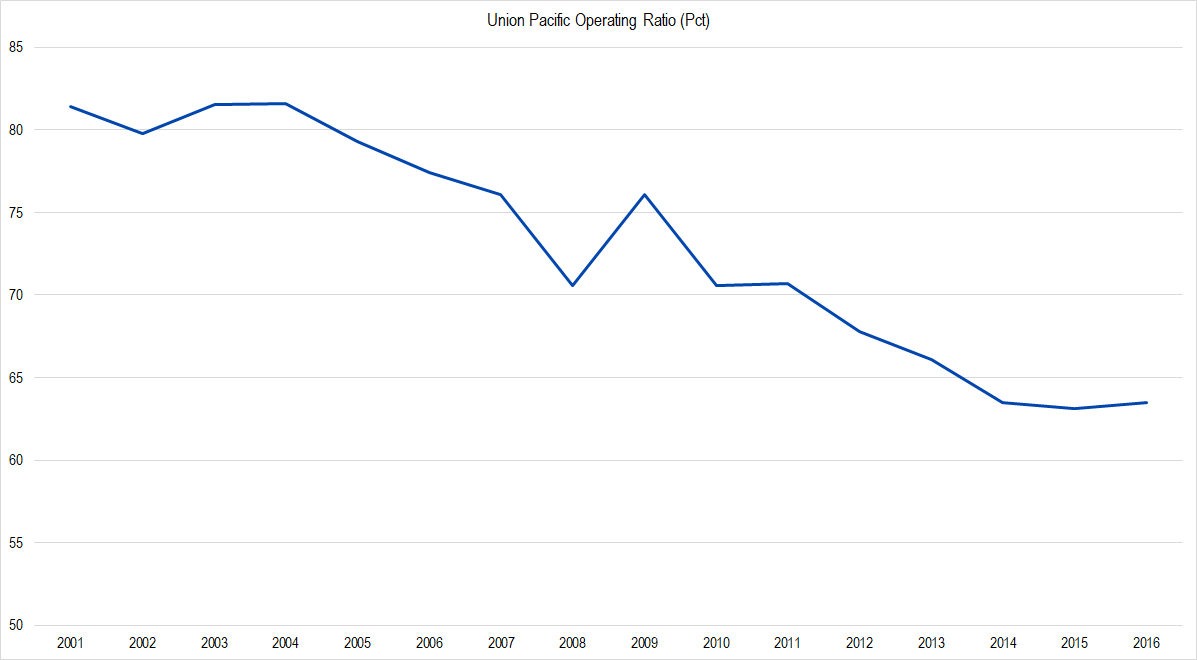

The company has a standing target of a 60% operating ratio (the proportion of operating expenses to revenues — a measure used by transportation companies) by 2019.

Figure 6. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis. The value for the first nine months of 2017 was 63.2, slightly better than the first nine months’ value for 2016, 64.1. 2016’s full-year operating ratio value was 63.5.

The fact that the company has been able to retain an operating ratio in the 63% range even as its business has slowed down is a testament to the company’s improved operating effectiveness and to its ability to retain pricing power as a virtual monopolist in many markets.

However, notice that even as revenues are up by around 7% this year, the company has not been able to move the operating ratio down much. From our analysis above, we believe part of the reason for the reduction in operating leverage this year has to do with excess capacity in all but a few of its important routes, coupled with persistently low diesel fuel prices (which have lowered the firm’s ability to pass through costs to shippers).

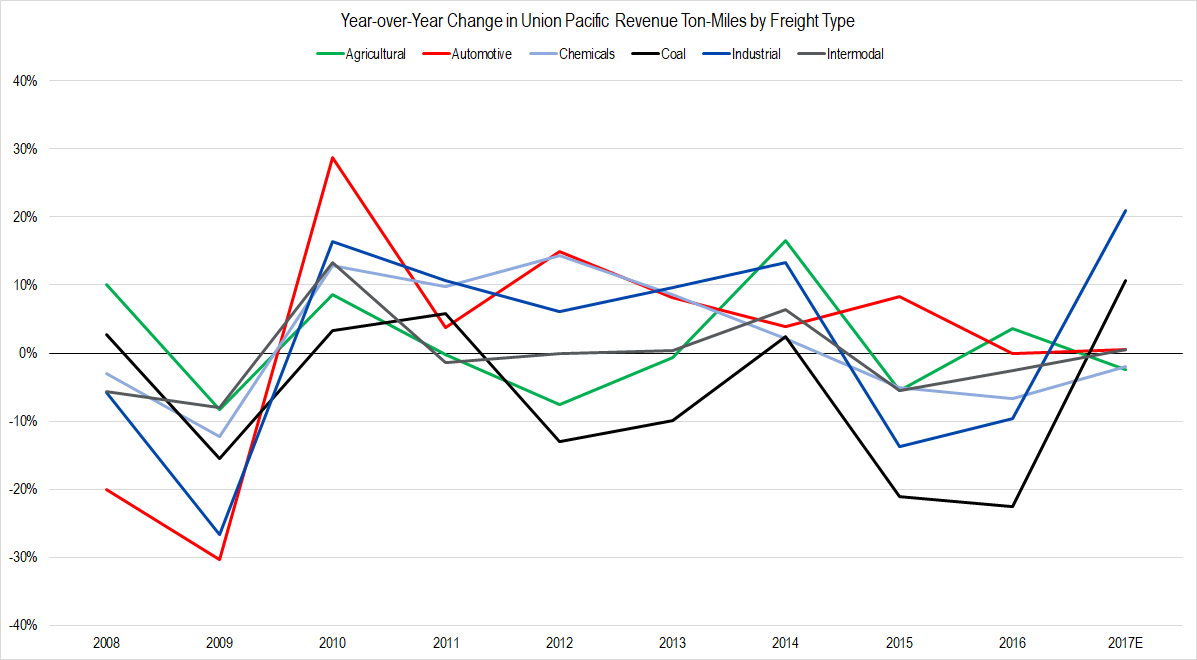

This chart shows the year-over-year change in the company’s revenue ton-mileage per freight type.

Figure 7. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

The chart is noisy, but the strongly increasing volumes for Coal and Industrial are easy to spot. Note that volumes in all other freight types are hugging flat-line or are slightly negative.

In terms of Union Pacific routes, this means that the routes carrying frac sand to Texas and the routes carrying coal out of Wyoming are packed, but other routes are underutilized.

Figure 8. Source: Union Pacific Investor Guide

If utilization on the entire network picks up and the company is able to retain its pricing power, we think it is possible for it to reach its 60% operating ratio goal by 2019. If, however, utilization remains spotty, it looks like it will be hard for the company to hit its goal as it seems to have wrung out most of the easy efficiencies from its network.

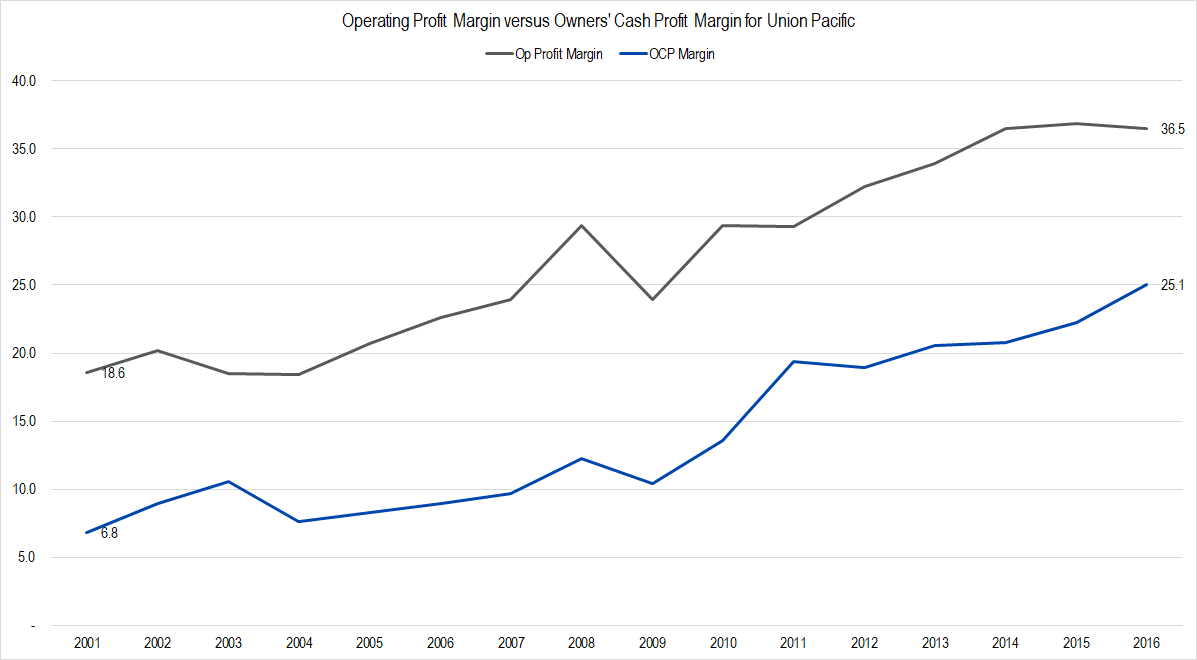

For our valuation, we need to triangulate what the OCP margin will be if the company is successful lowering its operating ratio. A comparison of OCP margin to operating ratio shows a pretty consistent relationship.

Figure 9. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

Over this period, OCP margin has seen an 18.3 percentage point widening versus a 17.9 percentage point widening for operating profit margin (the inverse of the operating ratio). We will keep this relationship in mind as we adjust our valuation model.

Taxes

With the Republican tax bill being discussed as I write this, it’s worth pointing out that a change in tax policy may have an effect on upon Union Pacific’s Net Income, which would in turn have an effect on Cash From Operations and Owners’ Cash Profits.

It is worth pointing out that the “tax plan” is still two plans and, in fact, that a lot of the details are still being worked out. As such, it is ridiculous to spend too much time trying to figure out what the effect of the passage of tax legislation will be until we know the specifics of the legislation. For this analysis, I’m drawing from a summary of the plan by the Tax Foundation and assuming that the statutory rate will come down to 20%, but that Interest Expense will no longer offer a tax shelter.

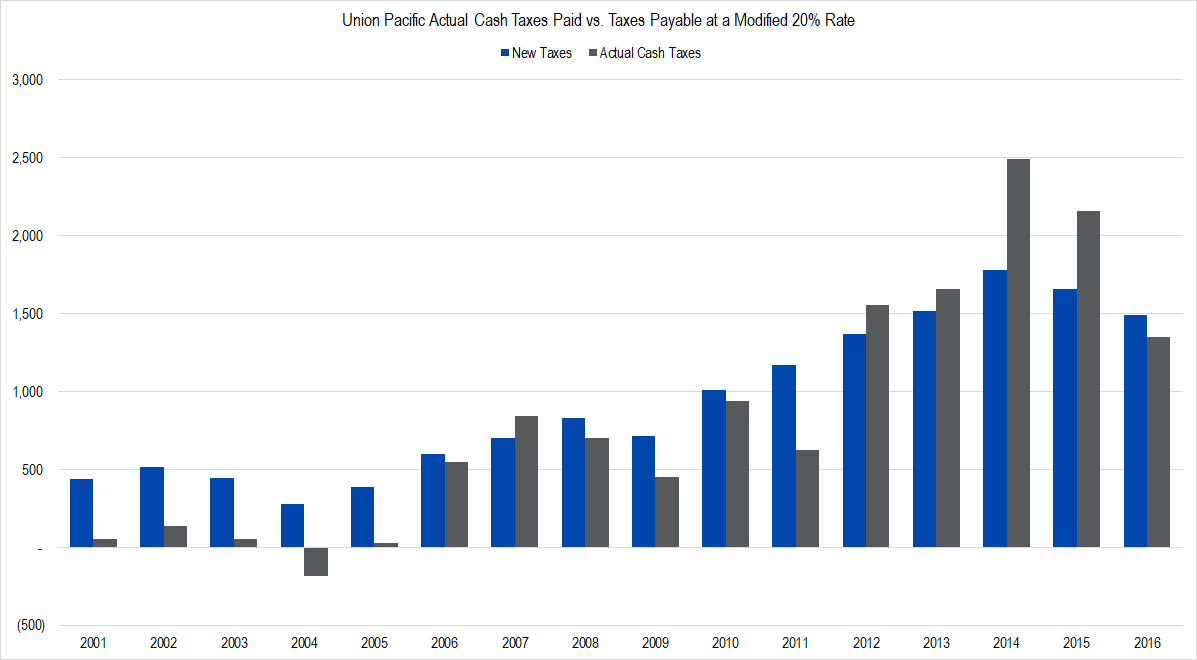

Using these assumptions and no other, here is what the actual cash tax paid by Union Pacific versus what it would have paid under the new legislation.

Figure 10. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

You can see that the “New Taxes” are considerably higher than the actual tax companies paid in many years — especially early on in the series. Because the interest expense was a relatively small part of pre-tax earnings in the boom years of 2012-2015, the new tax regime would have helped Union Pacific.

While I won’t spend a great deal of time on this, it’s worth noting that using these simple assumptions, the new tax plan does not look like an undiluted positive for the firm, especially if the firm takes on more debt.

Including the new tax rate into our calculation of OCP, we find the following difference in OCP margins.

Figure 11. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

We will keep this factor in mind as well when we model our valuation scenarios for Union Pacific.