The option investment we originally published to our Framework Investing members on April 11 of this year and detailed in a series of case study articles is expiring today!

When we originally invested in IBM’s downside potential by selling a put option, IBM was trading just at the $155 / share mark. As we explained in our article explaining the two rules of thumb for option investments, we decided to sell an At-the-Money put option with a tenor (i.e., economic life) of about three months.

In exchange for accepting IBM’s downside price risk, we received $7.80 of option premium, which I think of a subsidy to buying the shares of the company. In the case of IBM, our subsidized purchase price for the shares worked out to be $147.20 / share (I call this price our “Effective Buy Price” or EBP).

The transaction generated an immediate unrealized gain as IBM’s stock rose in anticipation of strong first quarter earnings numbers. In a seemingly continual attempt to test my equanimity and resolve, the market gods saw fit to slash IBM’s price as soon as IBM published its results on April 18.

Figure 1.

Just before the end of June, an investor who owned put options on IBM decided to exercise them, meaning we ended up buying the shares at our EBP of $147.20. As detailed in this article, the option assignment allowed me to squeeze a little more premium out of the position, as I was able to sell the call option struck at our original $155 / share strike price and receive another $0.11 / share of premium. This transaction – known by many as a “covered call” – allowed me to retain the same risk exposure as my earlier sold put and lowered my Effective Buy Price to ($147.20 – $0.11 =) $147.09 / share.

Yesterday, IBM reported results for its fiscal second quarter and the market gods gifted me with a nice pop in the share price – moving above $150 / share intraday and settling just shy of that level. As I write today, the stock is drifting down modestly and trading at around $148 / share, but it looks as though the original investment will at least break even and may even generate a slight positive return.

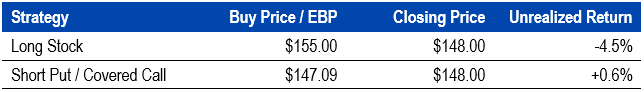

Assuming the stock closes at exactly $148.00 / share today, my returns versus the returns of a stock owner who bought the shares at the same time I entered my investment look like this:

Table 1.

An option investor in my position now has a few choices:

- Immediately sell the shares on Monday morning and realize the profit or loss on the position, using $147.09 / share as one’s buy price.

- Sell another “covered call” on the shares – extending the original transaction by another three months or so and further reducing one’s Effective Buy Price.

- Do nothing in the option market and continue to hold the shares.

Thinking about these choices, I immediately discarded the first. As I wrote in a note to Framework Members yesterday, the company’s operational results still look like they are tracking well with a valuation range associated with our best-case revenue assumption and our worst-case profitability assumption. If we are right about this, the intrinsic value of the company would be somewhere between around $162 / share and $194 / share, with a midpoint of around $174 / share.

Loading...

Loading...

Selling an asset that is worth $174 / share for $148 / share doesn’t make sense, which made the choice of selling out of my IBM position a no-brainer.

Regarding selling another covered call, by doing so as soon as the present option expires, I “roll” my position – maintaining an identical risk exposure as my original investment.

If the stock settled above $155.00 / share today, I would have stood to realize a gain on my original investment of 5%, which would have annualized to around 20%. As it stands, the original investment will offer a gain of less than the original, so even if I roll the transaction, for a full year, my actual gains will be less than the annualized value I calculated up front.

We find that there are almost always frictions of this type using this strategy, but if we can generate annual returns of half the annualized rate we calculated at the outset – around 10% or better – using this strategy, we will be in good shape, especially when compared to the yield on stocks or bonds right now.

The one thing about which an option investor must be careful when rolling a covered call investment is that the strike price at which one sells the second option must be equal to or higher than our Effective Buy Price.

If our Effective Buy Price is higher than the strike price at which we sell a covered call, we have agreed to “Buy High and Sell Low” – exactly the opposite of what a good investor would do!

I still think that the company has a way to go before it is obvious whether its investments in AI generate brisk cash flow growth in the medium-term that would put the value closer to the upper end of our range.

Because of this assessment, I will probably decide to write covered calls on my full position of four contracts. Those who are more optimistic about IBM’s medium-term growth might choose to only cover part, or even none of their position with call options.

We will continue to update this case study series with our updated valuations and transactions in IBM! Won’t you follow along with us?