The following is an excerpt from IOI’s most recently published Institutional Report on Express Scripts Holdings (ESRX), which was originally commissioned as a piece of bespoke research from one of our institutional clients.

It covers the competitive dynamics not only for ESRX, but also for the Pharmacy Benefits Managers industry in general. We find…

- Express Scripts is the largest player in an industry (the Pharmacy Benefits Manager or ?PBM? industry) that exists thanks to structural inefficiencies in the way prescription pharmaceuticals are marketed and consumed.

- PBMs have served an important role in bringing down the cost of prescription drugs over the last twenty years. Demand for their services from institutional purchasers of medical products and services has driven rapid growth for PBMs. However, the industry has matured, so future growth will be slower.

- The three largest PBMs account for at least 75% of prescription pharmaceutical purchases in the U.S. The industry is largely a zero-sum game ? the only way remaining to materially boost growth is by capturing a client from a competitor.

Express Scripts? business is essentially that of an arbitrageur an opaque, inefficient market, and its ability to generate economic profits is due to the intellectual property it has developed through years of operation and through multiple rounds of acquisitions. The business can seem confusing, but framed in these terms, it is not.

What started out as a simple, bookkeeping function has turned into a business that holds increasing power in the healthcare sector. Express Scripts and its Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) competitors stand at the nexus of the market for prescription pharmaceuticals. This vantage point has made it possible for them to jointly drive down prescription drug prices while finding opportunities for their own companies to prosper.

As the PBM industry has consolidated, PBMs have developed scale advantages that allow them significant leverage over drug manufacturers and have allowed them to actively influence the healthcare recommendations made by physicians and the purchases made by consumers.

Data ? the Core of Express Scripts? Business

Express Scripts generate revenues through three main sources ? administrative fees, the sale of generic drugs through online pharmacies, and rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Of these revenue sources, online sales and rebates generate the lion?s share of profits, but the engine which allows these profits to be generated is the business for which it receives administrative fees.

On the most basic level, Express Scripts earns fees by keeping track of available prescription drugs and substitutes on one hand, and of the drug purchases made by Express Scripts? clients? members on the other. Express Scripts? clients are insurance companies and corporate health plans. These clients pay a portion of their own members? fees or premiums to Express Scripts as an administration fee.

While only about 1-2% of Express Scripts? revenues are typically generated through these fees, this business forms the core of it and other PBM?s ability to compete. The data required to check for drug substitutions and interactions and to keep track of patients? drug usage is a goldmine in the hands of a PBM.

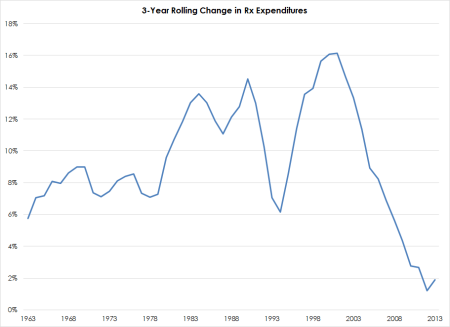

The first way in which Express Scripts monetizes this data is by structuring drug plans to push drug buyers toward less expensive alternatives where available. Thanks to the increasing reliance on PBMs and their intelligent structuring of drug plans[1], the phenomenal growth of U.S. prescription drug expenditures has slowed significantly over the past 10-15 years as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Rolling Year-over-Year Change in Prescription Drug Expenditures. Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, IOI Analysis

(The huge uptick in the early 1980s corresponds to a legal change in Reagan?s first administration which made it legal for university and other academic research institutions to sell patents to private drug companies. Before that time, drugs developed using public funds were public domain products, so the regulatory change effectively acted as a transfer payment from general taxpayers to owners of pharmaceutical manufacturers. If you are a U.S. taxpayer, you owe it to yourself to own Big Pharma?)

This ability to cut costs provided real benefits to PBM clients; this value add was the main driver of the PBM industry?s rapid growth over the past generation. However, even as PBMs were earning fees for helping their customers cut costs, they realized that there was a way to boost their own income and still keep clients happy. This is the second way PBMs are monetizing their prescription data.[2]

To understand how this works, we have to stick our toe into the inner workings of the opaque and complex system for providing and paying for prescription pharmaceuticals in the U.S.

A Convoluted System ? Fuel to the ESRX Fire

Most companies? business models are pretty easy to understand. They provide some product or service which have some direct or indirect competitors. Buyers of the products and services compare the competitive offerings and make a purchase decision which most closely satisfies their needs and / or wants.

In the case of prescription pharmaceuticals, however, this simple model is convoluted by the fact that the user of the product (patient) has little sense of final cost and the purchaser (insurer) of the product has little power over the purchasing decision.

The party making the purchase decision usually does not have the medical training necessary to assess the relative merits of the product and has no way to compare its final costs anyway. The purchaser knows how much it is charged, but has limited ability to suggest an alternative. The main way the purchaser has of influencing the drug prescription process is by charging its own customers a higher fee for the insurance services it provides. And because most medical insurance is heavily subsidized by the companies employing the end users of the drugs, even higher insurance premiums do not usually have a large economic impact on the end users of the drugs anyway.

PBMs ? ESRX included ? standing at the nexus of all these payment and purchasing transactions, realized that in some cases, it could save insurers money, satisfy patients, and increase their own profits substantially. They do this in two ways ? mail order pharmacies for recurring prescriptions of generic maintenance drugs and through rebates on competitive drugs.

Just in the same way that it is cheaper for Amazon.com to sell to its customers than a neighborhood bookstore, it is cheaper for online pharmacies to sell prescriptions than a neighborhood pharmacy. The latter must keep a pile of inventory handy ? bandages, over-the-counter medicines, hearing aid batteries, and the like ? as well as maintain a physical storefront, and these inputs raise costs for physical retailers. All PBMs run online pharmacies and, through the structure of their prescription drug plans, can channel users into its clients? members into purchasing generic drugs for maintenance prescriptions through these outlets.

Because online pharmacies? costs are much lower than those of neighborhood pharmacies, offering a modest discount on the prices charged by brick-and-mortar retailers will allow them to generate a healthy profit while still showing relative cost savings to their end clients. (Some pharmacists also believe that Express Scripts charges a higher mark-up for generics sold to retail pharmacies, allowing it to gain even more handsome profits from its own mail order sales.)

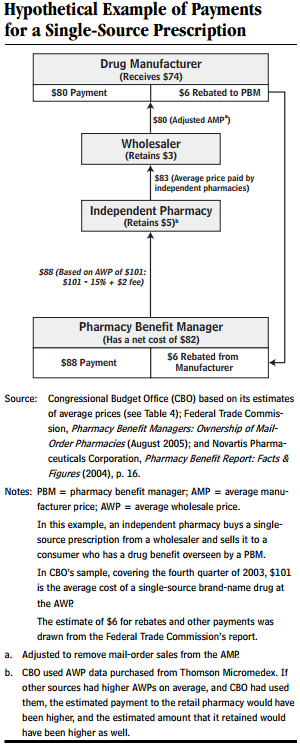

The other opportunity for PBMs to generate opportunistic profits is through a system of rebates on drug purchases from the drug manufacturers. This is complex enough to require a detailed illustration, which can be found below.

PBMs have developed significant negotiating leverage over drug manufacturers despite the fact that (other than their online pharmacy divisions) they do not take possession of drugs, but simply process payments.This leverage is generated through the PBMs? ?formularies? ? a list of drugs that the PBMs include in drug plans. Sales of drugs can be helped or hurt depending on whether a drug appears on this formulary and in which tier it is placed. As such, drug manufacturers agree to rebate some portion of the purchase price of their drugs to the PBMs as a marketing tool.

The diagram in figure 2 of a hypothetical rebate transaction taken from a Department of Labor publication gives an illustration of how these rebate transactions work. As you can see from the footnotes, there are various benchmark prices for drugs and the details of the calculation of the rebate are tedious.

Two parts of the rebate process are not included in this diagram, but are also important. First, the diagram shows the PBM making a payment of $88, but does not show that the insurer or health plan is paying the PBM. The rebate received from the manufacturer may or may not be fully or partially passed through to the insurer ? these details are contractually specified between the PBM and its client. The degree to which rebates are passed through are opaque, and until a recent regulatory change and several multi-state lawsuits brought by state attorneys general, the entirety of the rebates were retained by the PBMs.

The other part of the transaction not shown in figure 2 is the copayment made by the patient to the pharmacy. This is usually retained by the pharmacy and that amount is deducted from the payment the PBM ends up making to the pharmacy. From my reading, it does not seem like this copayment is any more than a pass-through ? in other words, it is value neutral to the PBM.

Regulatory Risk

Despite PBMs? important role in the provision and payment of prescription pharmaceuticals, it is one area within the Healthcare sector that is subject to only minimal government regulation.[3] The industry spends a good amount of money in Washington, hiring K-Street consultants and making contributions to political candidates, to make sure this light regulatory touch stays light.

While it is true that PBMs have helped hold down drug costs for insurance companies and other healthcare provider companies, critics say that PBMs are bullying pharmacies and drug manufacturers alike into financial arrangements beneficial to the PBMs and detrimental to other players in the system ? ultimately lowering the effectiveness of the healthcare system as a whole.

Pharmacies complain that PBMs are taking advantage of the complex pricing systems and multiple payers and paying pharmacies at a lower rate for drugs dispensed than they are charging the insurance companies. This ?spread pricing? has been the impetus of the states? attorneys general lawsuits mentioned above. In addition, there is a significant conflict of interest inherent in the PBMs? captive mail order pharmacies (since drug plans? price incentives essentially create demand for the PBMs? own pharmacy services) that strikes some as being a breach of fiduciary duty on the part of the PBMs.

In light of these issues, the risk that the PBM industry will be subjected to increased costs associated with the imposition of regulatory controls does exist. However, while increased regulation may be in the cards, it is unclear to us whether the associated costs will end up being borne by shareholders of PBMs or passed through to its clients (through higher administrative fees) and / or network partners (through contracts less favorable to pharmacies).

[1] Most drug plans are structured in a three-tier system. Generic drugs carry the lowest copayment, other drugs have a higher copayment, and specialty drugs, the highest. The copayment is the only cost the ultimate user of the drugs sees, so by structuring the tiered fee system in an intelligent way nudges drug users toward generic brands rather than to the Tier II name brands when generics are available.

[2] PBMs also monetize their data by selling information about drug usage patterns to drug companies to help them in their product development and marketing efforts. This makes up a relatively small portion of revenues, but what revenues it does generate fall almost directly to the bottom line.

[3] As a Medicare Part D provider, it is subject to regulatory oversight and reporting, as well as to reporting related to its gathering and use of confidential patient data.