The other day, I had a vigorous Twitter debate with John Authers, a journalist who writes for arguably the best daily newspapers in the world, The Financial Times. Authers wrote a story entitled Fears grow over US stock market bubble that quoted Nobel-prize winning Robert Shiller regarding his famous Cyclically-Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio (CAPE).

In a nutshell, Authers’s argument is that because the present value of the CAPE is much higher than its long-run average, the U.S. market is destined for a big fall. While I generally love Authers’s work, I think his take on the CAPE is over-simplistic. In this article, I provide a brief, common-sense refutation to Authers’s argument and post a research paper regarding the CAPE that I published while at YCharts.

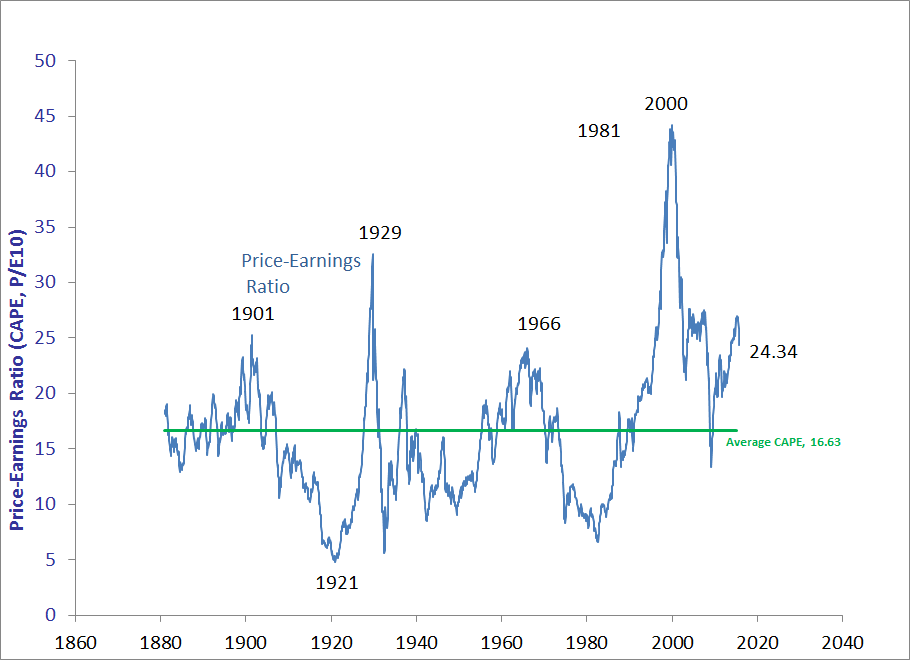

Here is a graph of the CAPE drawn directly from the data posted on Professor Shiller’s website:

These are monthly data, and I have added the long-run average value for the entire series. Most graphs of the CAPE show annual values and the average value of the CAPE during 2009 was 16.92 — nearly 0.30 points higher than the average value. The low value of 2009 was recorded in March when the S&P 500 closed at 13.32 — almost precisely 20% below the long-run average. By July of 2009, the CAPE was once again above the long-run average by just a bit.

Looking at this chart and thinking back to your own investing experience, did 2009, on average, seem like a year with generally fairly valued stocks? The 2009 CAPE value of 16.92 would imply, given Authers’s argument, that 2009’s average S&P value of 946.74 (as recorded by Shiller) was just about right. Certainly, March 2009 showed a CAPE value that was under the long-run average, but remembering back to some of the happenings at that time (companies trading for less than net cash values, money market mutual funds “breaking the buck,” etc.), it seemed to this observer to be a much more extreme undervaluation than a mere 20%.

This argument is an anecdotal one, but I do not think it is entirely unreasonable. The concept of “average” is a simple mathematical model. Simple mathematical models provide simple predictions and work best when they describe a consistent process (like the length of bees’ tongues or the decay of radioactive materials). Economic activity is not necessarily a consistent process — the development of Internet technology and increased efficiency since the mid-1990s changed the pace and scope of economic activity in a way never before experienced by humankind. Is there a good reason why the average CAPE value during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration should have bearing on predicting a reasonable CAPE value in 2015?

Shiller’s underlying point about markets is a valid one. Namely, equity market pricing must reflect the capacity of an economy to generate wealth in the form of corporate earnings. When large distortions appear — the irrational exuberance of the dot com tragedy, for instance — a correction is bound to occur.

So let us take a look at the present value of the market vis-a-vis the growth of wealth over the last 10 years. S&P 500 earnings as of March 2015 were roughly 37% higher than average earnings for the preceding 10 years. Over the preceding 10-year period, the S&P 500’s average value was 1289; increasing that average price by 37% gets us to 1,766 — less than 7% below the value of the S&P 500 as I write. If we say that the most recent 10-year period is a valid starting point to calculate a base level for the capacity of S&P 500 companies to generate earnings, present market levels appear roughly fairly valued, rather than wildly overvalued as Authers suggests.

This is a back-of-the-envelope calculation, but again, it seems valid in spirit and in fact.

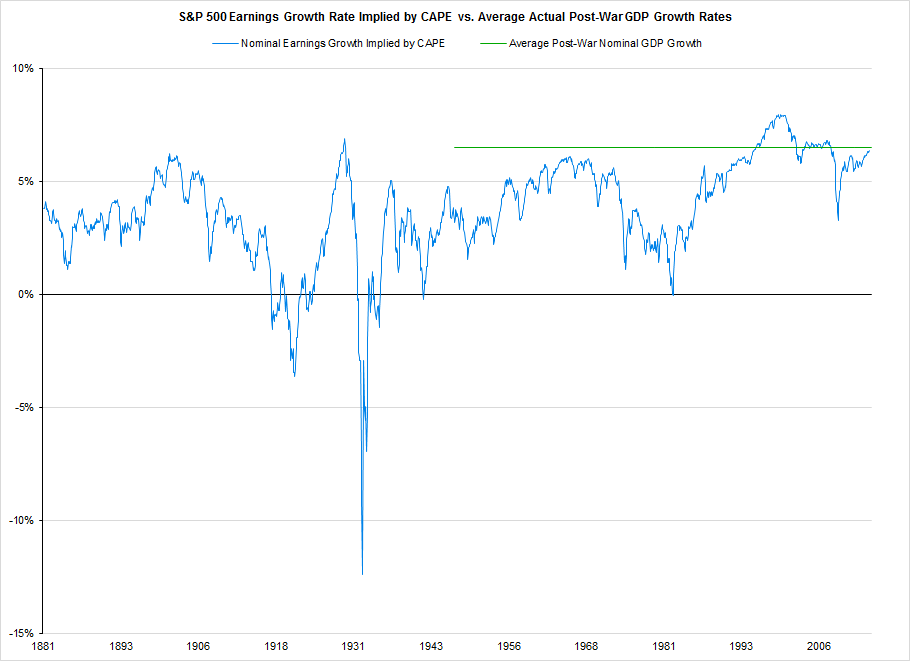

The attached research report on CAPE takes a more careful look at what the CAPE may or may not imply and also suggests reasons why the post-War average CAPE values may have been demonstrably too low. My findings that pre-War CAPE values were a more accurate predictor of future economic activity agree with observations that Keynes made in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money regarding an increase in market efficiency when managers of a company make up a large proportion of its shareholder base.