Warren Buffett once said that…

An investor’s success is in direct proportion to the degree to which he understands the investment.

Like a lot of the Oracle’s statements, this bite-sized morsel of wisdom seems sensible at first, but turns out to be difficult to operationalize for most people. How does one go about understanding an investment, after all? Buffett gives no clear instruction for that!

This is where IOI comes in. I’ve spent more than 20 years looking at companies for hedge funds, investment banks and as an independent analyst with Morningstar and YCharts. Recently, I’ve been working on a valuation of Gilead Sciences (GILD). This is a company that was suggested by several subscribers, but which I have never followed or owned. On top of that, I only have a layman’s knowledge on the industry.

With such little understanding of the industry, I thought it would be a terrible pain to value Gilead – in fact the names of the drugs and compounds are driving me crazy as they are a terrible pain – but I found that sticking to the process that I always use and teach in the IOI 100-Series courses makes it easy. That’s right, I said “easy” and here is why.

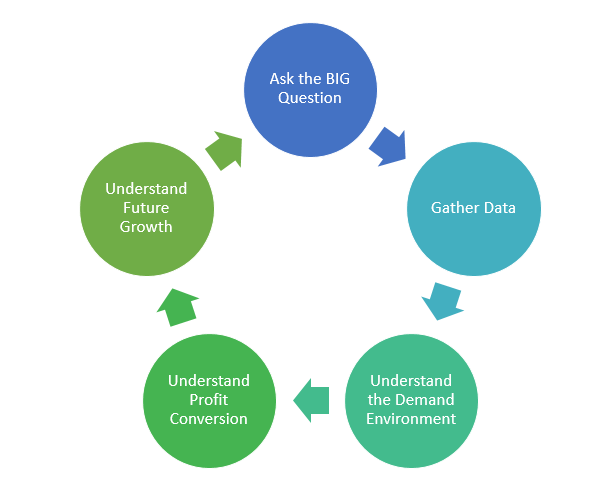

The process is straight-forward:

- Ask the big question

- Gather data

- Understand the demand environment for the company’s products

- Understand how efficient the company is in converting its revenues to profits

- Understand its recipe for growth

Ask the Big Question

As a seasoned analyst, asking this question at the top comes naturally to me now. But, at the start it was not always clear what I was looking for when I picked up a company for the first time. Intelligent investors know that the value of any company is equal to the value of it’s future cash flows discounted back to the present – because the value of a dollar today is greater than one I receive later (time value of money). Since this is true, the big question that follows is, “How and why does this company and the industry it is operating in exist and generate cash flows?” I have to understand these inputs in order to understand the company’s current financial performance as well as be able to forecast performance into the future with some reasonability.

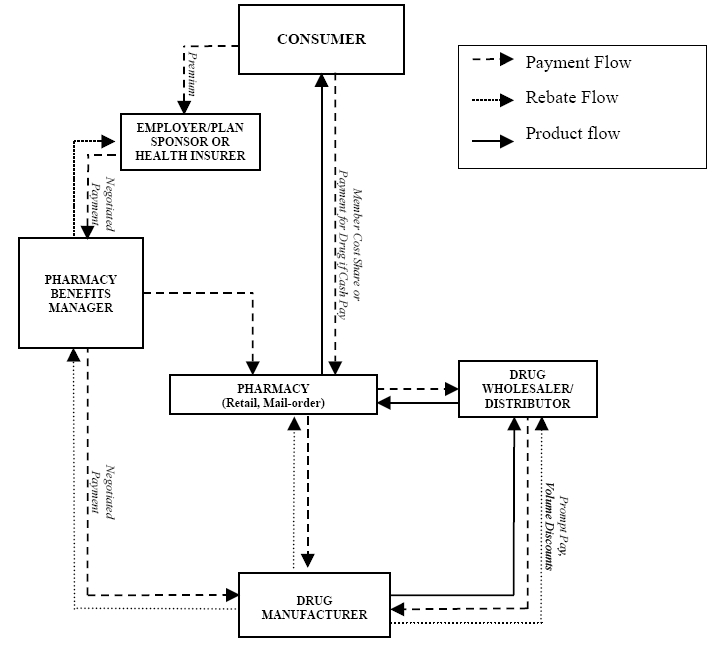

The answer to this, for most companies, can be found by reading its financial statements (the form 10-K and / or the 10-K of the 800lb gorilla in your target company’s industry) combined with looking online for industry level business summaries and news stories. Often times there are relatively learned blogs from consultants who are devoted to an industry. By first looking into these very basic things you will get a feel for the “directness” of the business. For example, how Encore Wire (WIRE, a company we reviewed for our members in a Small Cap Diary report) makes money is a far simpler “flowchart” to draw than how Express Scripts (ESRX) or Gilead accomplishes the same task. By taking time to first understand the playing field, you gain perspective over the next four steps. You also start building an analysis framework for yourself because you can lay out the different dependencies on which a business’ revenues rest.

Figure 1. Source: Shmula.com

Gather Data

Most high-level data are available online for cheap or free. I use YCharts to get most of my operational data – historical revenues, historical Owners Cash Profit (OCP) and historical average price. YCharts is not free, but it provides reliable data and history that goes back much further than free sources; also, because I was Director of Research there, they were good enough to build OCP and OCP margin into the system, which makes it easy for me to use.

Data regarding investment spending – acquisitions, anti-dilutive stock buybacks, money spent on joint ventures, and the like – is not available from a data service, so I open up the financial statements to get those data. We have a video about that data collection process in the video section of our site, and we intend to provide these data to subscribers as part of our IOI Tools application, which we are building now.

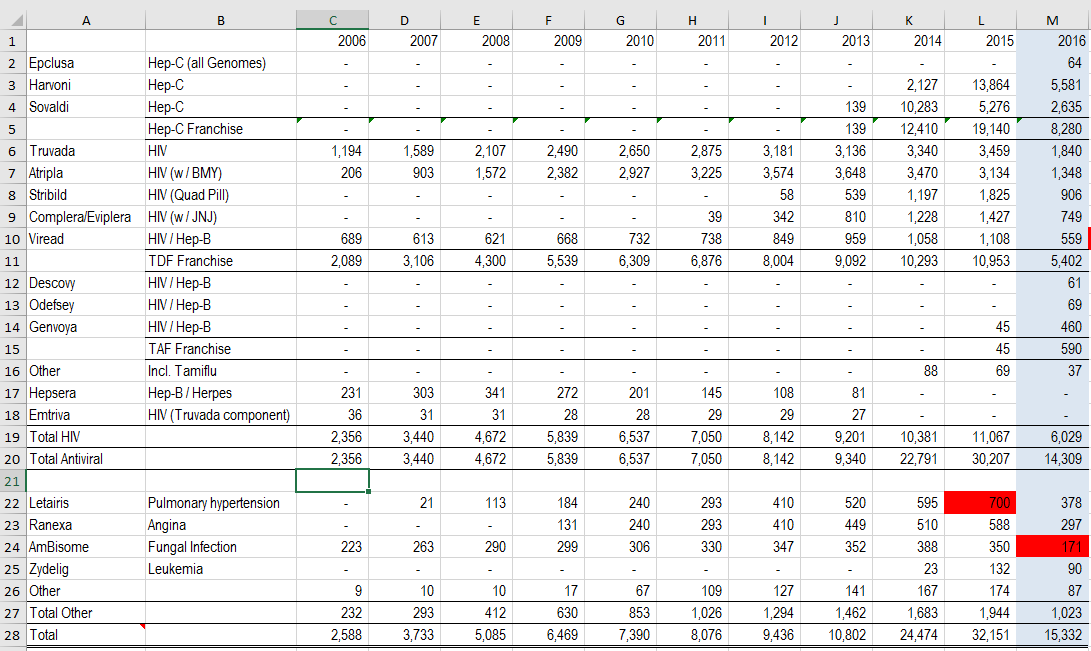

Last, while I’ve got the financial statements open, I look for data regarding revenues broken down by business segments and / or by regions (I just search the file for “segment” to find it quickly). Gilead does not report on a segment level, but does split out sales for different products; I copied the data into a spreadsheet as shown below:

Figure 1. Source: Company Statements, IOI Analysis

This looks like a lot of work, but it only took a few minutes all together to get the data in and it also helped me to start in on the next step – understanding the demand environment.

Understand the Demand Environment

The first step in understanding Gilead’s products was by going back and figuring out what diseases each of the drugs treated (you can see that in column B of the figure above). This helped me get familiar with the molecules used in the drugs, the history of the firm (you can see that some drugs’ revenue streams trail off while others pick up), and when certain products were incorporated into new ones (e.g., Emtriva sales trail off but become a part of the fixed dose compound called Truvada). Wikipedia is great for this and I donate money each month to the Wikimedia Foundation because I use its resources so heavily in my research.

After I finished looking at each of the products and what they did, I shifted my attention to the revenue amounts. Looking at the spreadsheet above, you’ll notice something striking – the “Hep-C Franchise” is blank for most of the company’s history, and all of a sudden in 2014, rockets up to surpass all of its other products.

This realization was my jumping off point to learn about the company. The “learn about the company” part of the process is decidedly not linear; it mainly involves reading news stories, brokerage reports, company announcements, other companies’ announcements, conference call transcripts, and some parts of the financial statements. It also took me past Gilead’s Hepatitis C franchise (which is truly an amazing story, by the way) to learn about the company’s HIV franchise (also amazing) and some of its other areas of research and testing.

A good part of this reading is finding a mention of something and going to try to find confirmation of that in another source. For instance, let’s say an analyst makes some claim about the company’s competitive advantage in some field; I will search through for news about competitors’ products and try to find some impartial information that directly or indirectly shows that contention is true or false. My goal here is to understand the degree to which Gilead is providing a product that uniquely meets the demand environment.

This is the part of the process that takes the most time and effort, especially for me just learning about this industry for the first time. The nice thing about the time spent on this is that it makes my process in the future much more efficient. If the company announces something about its new Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) treatment Epclusa, I have a much better handle on why that product is an important part of its product line-up and what impact, if any, that announcement might have on my thoughts regarding the company’s future revenues.

I also found that my research on another firm – Express Scripts – came in handy while I was researching Gilead as well. This is another example of the efficiency of doing deep research – understanding one company well makes it easy to understand other companies at a later point.

Throughout all of this, the one thing that I’m careful to do is not to get too far into the weeds regarding the scientific background of all of these compounds. My job is to try to assess some reasonable, accurate estimates of short-term revenue growth in this stage of the process (and to think a little about future cash flow growth), not to try to prove that I’m as smart as a microbiologist. A lot of analysts and portfolio managers want to show that they are the smartest people in the room, so sometimes dig far too far into detail about technical specialties.

Figure 3. Source Wikipedia

The funny thing is that this rabbit hole process is mostly only a balm to their own vanity. There is no way for someone who is not trained and working in a specific field – whether that is antiretroviral drugs or coal mining – to know as much as someone who specializes in the industry. The key is to understand the advantages of a certain product well enough to know how the sales of that product are likely to change in the future – not to try to pass yourself off as a microbiologist or mining engineer yourself.

This step in the research process essentially is open-ended. As time goes on and I am listening to conference calls or reading articles, I mentally check the information there against the mental model I’ve built for the company and adjust the mental model – or completely revisit and revise it if the new information forces me to do so.

Understanding Profit Conversion

This is an easy step in the valuation process. Companies are very mechanical – for a given level of revenues coming in, they generate a certain level of profits. Over time, profitability fits clearly into a well-defined band. This does not mean that bands cannot change over time (Oracle is an example that has seen several upward steps in its profitability), so one needs to think about the dynamics behind the profit conversion a bit as well and whether it has the potential to increase or decrease.

I don’t spend a lot of time analyzing profits (by which of course I mean Owners’ Cash Profits) and that is directly opposed to the way most Wall Street analysts work. The reason for this discrepancy is that the Wall Street guys need a precise profit number on which they can apply some multiple – this is the mechanism by which they derive target prices.

If one rejects the idea of multiples-based valuations – and I do – there’s no point in getting into the weeds with near-term profitability. Especially accounting numbers like Net Income or the hated EBITDA are affected by accounting conventions and often miss the cash-based economic essence of the business. The most important thing to understand about a company is how the cash flow of a business will grow into the future; to do this, you need to understand a reasonable range for present profit and cash flow levels, since the present levels are the jumping off place for future profit and cash flows.

Understanding the Recipe for Future Cash Flow Growth

This is the hardest step for most firms that are not in a structurally stable businesses and is the part of the process most subject to error. Difficulties in forecasting future growth for firms in emerging industries is, I believe, the reason that Buffett simply doesn’t invest in these kinds of firms.

One of the strengths of the IOI valuation methodology is in fact that we are never trying to pick the one, exactly right medium-term growth rate. Picking best- and worst-case estimates is enormously freeing and allows us to be roughly right rather than precisely wrong.

As those who have been through IOI training programs know, to derive these best- and worst-case estimates for future cash flow growth, we look at how the firm is investing its owners’ profits in the present. If the investment environment is rich and the managers pick investment projects skillfully, future growth will probably be relatively brisk versus the growth rate of the economy at large. If there are not many good investment opportunities, the management’s investment objectives are off-base, or the company has a history of botching investment projects, future growth will probably be relatively slow.

For Gilead, its future growth depends upon its research and drug pipeline. This is a very hard thing for a layperson like me to get a handle on, so I did two things:

First, I asked people who do know something about the industry for their opinions on the dynamics of biotechnology investments. Of course expert opinions are anecdotal and should not be considered definitive, but in the case of my analysis of Gilead, it did call into question the common meme in the investment business that Gilead has the ability to consistently and accurately pick the next big thing in a certain field.

Second, I wrote the Gilead Investor Relations people a note and asked them questions about the process that went into the 2011 investment in Pharmasset that built the company’s enormously successful HCV treatment franchise. Again, the answers I get from the IR team will be anecdotal and not definitive, but may inform my thinking about future growth rates.

Because there is a great deal of uncertainty in future growth rates for Gilead, our valuation range for the company is likely to be wide. A wide uncertainty range effectively raises the bar to making an investment because there is a greater chance that the worst-case valuations will be below the present price of the stock.

Summary

This may seem like a lot of work and you might question the necessity of it. I see this kind of research as a “capital expense.” It does take some time up front to understand a business and the dynamics of its revenues and profits. However, really understanding a business is the only way to consistently make good investment decisions.

If you don’t know what the value of a business is and how that value is generated, when the market price of the stock is rising or falling quickly, you will be like a deer in the headlights. Should I buy?! Should I sell?

At times like those, most people’s decisions turn out to be worse than the flip of coin; because we are all subject to a raft of behavioral biases, we are almost guaranteed to react in a certain way to a certain stimulus. Reacting that way may give us psychological ease, but is usually the source of regret longer term.