At the end of last month, I published an investment idea to the members of our service regarding Union Pacific (UNP). The investment expresses a bearish view on the company’s value based on my analysis as a long-time value investor, and is structured using option contracts.

One of the points I brought up in a summary published publicly is that, according to my analysis, the company had been able to generate enormous profits thanks to what I think boils down to un- (or under-) regulated anti-competitive pricing on part of Union Pacific and its Class I freight railroad peers.

My comment about Union Pacific’s pricing was only tangential to my valuation (it is a bullish element of it), but it proved to be contentious. A reader who had seen a summary of my valuation report called me a “socialist,” and people came out of the woodwork to tell me how wrong I was. One reader, a trader at a hedge fund, wrote me saying that my analysis contradicted that of a famous analyst at the premier sell-side research house on Wall Street, Sanford A Bernstein.

The Bernstein analyst, David Vernon, had written a 100+ page report in May 2016, which maintained that railroad pricing power was not a function of quasi-monopoly power, but of increases in trucking rates that allowed Union Pacific to undercut truckers while still boosting profits. Vernon provided pages upon pages of impressive scatterplots and statistical arguments to prove his point.

Despite all the scatterplots, his contention seemed suspicious to me. I decided to take a simple look. When I did, the picture that emerged was that of an unregulated monopolist.

Union Pacific: Portrait of an Unregulated Monopolist

When accused of monopoly pricing, representatives from the rail industry use what I call the “trucking argument.” Shippers, according to the trucking argument, always have another transportation option, so if they don’t like the price offered by rails, they can take their business elsewhere.

If trucks were a true alternative to railroads, we would expect the profit margins for both industries to be roughly the same. Competition drives out differentials in pricing as naturally as water seeks the lowest point. In contrast, one of the hallmarks of a monopoly is pricing that is significantly higher than marginal cost (i.e., profits are excessively high).

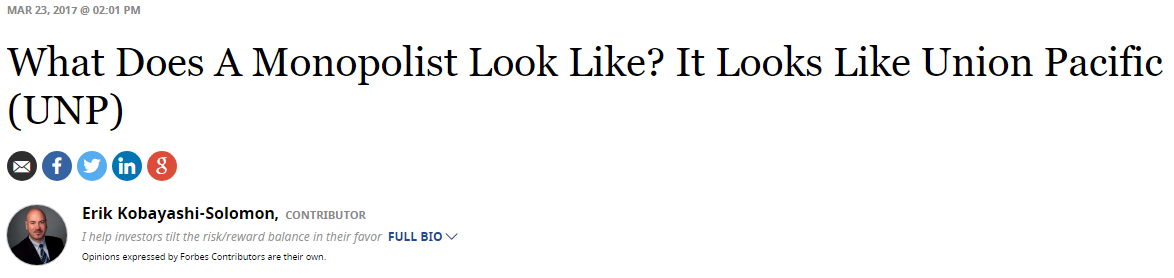

Here is the actual profit differential between Union Pacific’s Owners’ Cash Profits and an aggregate of publicly-traded trucking companies.

Figure 1. Source: YCharts, Company Statements, IOI Analysis

In the graph above, we can see that in the decade starting in 1990, Union Pacific’s profit margin was similar to that generated by trucking companies over the trailing twelve-month (TTM) period.

As deregulation rolled on and railroads were allowed to consolidate under favorable economic terms, Union Pacific and other Class I freight railroads could extract more profits from each dollar of incoming revenues. As of 2016, Union Pacific’s profitability was over eight times higher than that of trucking companies in aggregate (27.3% versus 3.3%).

Trucking is competitive with rails in one sense only – it involves the transport of goods from point A to point B. Judging by profitability, however, there is no competition between trucks and rail.

If Union Pacific is extracting monopoly profits from its shippers, it’s worth asking the question “How are the shippers’ profits doing?”

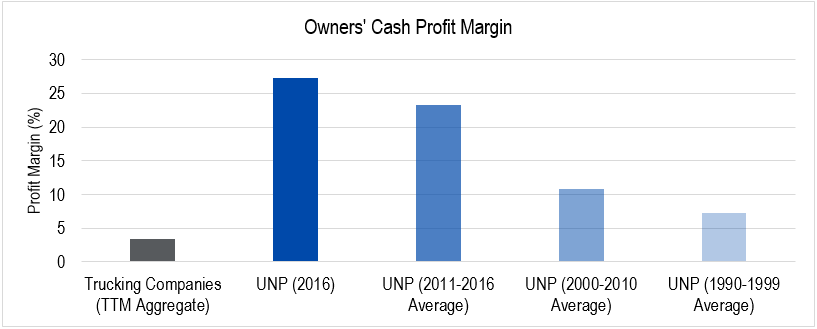

Figure 2. Source: YCharts, Company Statements, IOI Analysis

In Figure 2, I’ve selected just three industries that use railroads to ship products. These are shippers that are often “orphaned” (i.e., have access to only a single rail provider) and, because of either low value-to-weight ratios or safety concerns, can only effectively ship by rail.

The story Figure 2 tells is striking: If you own interest in a chemical, coal, or farm products company that operates west of the Mississippi, you should also own Union Pacific; some of your profits that would have flowed through to you as the owner of a coal company are being enjoyed by the owners of UNP!

Note that these graphs showing what look like large excess profits are not an absolute sign that Union Pacific is a monopoly. There are industries in which a low-cost competitor can act as a price taker and still generate more profits than a high-cost competitor.

For instance, a wind farm supplying power to an electrical grid will generate a much higher profit than a coal-fired plant because the input costs are so much lower. However, in this case, new wind farm competitors would soon start up so they too could earn excess profits. Eventually, the price of power would drop far enough that the coal plant could no longer remain profitable and only price-competitive wind farms would exist.

Railroads, however, exist in a very special environment – one in which there is never the possibility of a new market entrant. It would cost an estimated $1 trillion to reproduce the Class I railroads networks built over the last 150 years at significant public expense, and that’s even before the cost of land is factored in.

The Voice of an Expert

I’m just a stock analyst. I’ve never worked for a railroad or negotiated a contract as a shipper. There is no reason why you should listen to me any more than you should listen to the Bernstein analyst.

But if you won’t listen to me, listen to the words of Jay Roman, who runs a firm called Escalation Consultants. Escalation analyzes the rates charged by rails, then helps shippers negotiate more effectively with companies like Union Pacific.

According to Roman, shipping rates for rails have increased three times as fast as the increase in trucking rates since around 2004-2005, and he believes that railroads have started to price themselves out of some shipping business. In the old days, if cargo was to be hauled over 100 miles, it was more efficient to haul it by rail. With price increases, however, the break-even distance has moved closer to 500 miles (roughly the distance between Akron, Ohio and New York City).

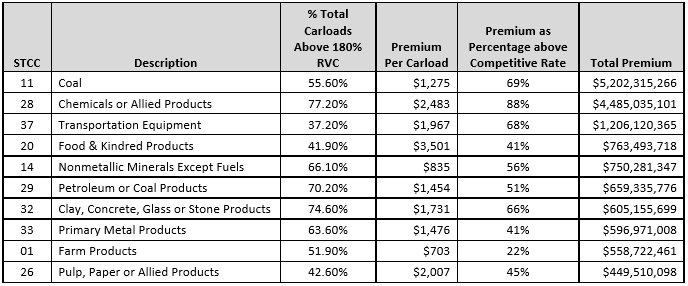

One table in Escalation’s 2014 report entitled Analysis of Freight Rail Rates for U.S. Shippers stood out to me:

Figure 3. Source: Escalation Consultants, 2014. RVC and “Competitive Rate” are technical terms. We encourage the interested reader to download a copy of the report for themselves.

The most important column in the table is “Premium as Percentage above Competitive Rate.” This table shows that, in the case of Chemicals or Allied Products, for instance, rates would need to fall by nearly 50% for them to be even statutorily defined as “competitive.” In a true competitive market, rates tend to be even below the statutory “competitive” rate, so would likely fall even more.

Have I Made the Bull Case?

You may think that I have effectively made a bull case argument for Union Pacific. Indeed, I think its pricing power gives the firm an immensely powerful positive valuation effect. That is why in May 2016, when I originally analyzed Union Pacific, I didn’t think much of a bearish investment in the company, even though it was just at the high end of what I considered a reasonable valuation at that time.

Now, however, we think that the advantage of Union Pacific’s pricing power is wholly offset by the threat of a trade spat with a major trading partner like Mexico or China under the administration of someone I have called the most anti-business president since Carter.

Union Pacific exists in large part because Americans like to buy so much cheap stuff from overseas producers. If prices rise due to tariffs, or if trade flows stop due to a trade war, Union Pacific will take it on the chin.

If and when that happens, I believe the company’s stock price will fall to one more reflective of the value it stands to create for its owners.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com

Discloser: The author of this article has a bearish investment position in Union Pacific’s options.