We’ve been soliciting comments from professional investors regarding the Framework article we published the other day regarding the proper rate at which to discount cash flows when valuing a company’s equity.

One of our members, Robert R., an institutional investor based in New York, responded to our call for comments, and the points he raises are very good.

Our exchange is posted here to provide more color to the original article. We cover topics such as how to handle a discount rate for REITs, equity discount rates during high interest rate environments, and how much to consider market timing when thinking about “opportunity cost” based equity discount rates.

Comments from Robert R.

I like the paper and you do raise some good points. I like to think of the ERP as “elusive”, essentially you can’t be right (or prove it) and everyone’s estimate is wrong.

- I have a few issues with using a constant 10% rate. i’ll bullet them:

Should we use the same rate for a company with distant cash flows, like Amazon, and a high quality REIT with visibility into nearer term cash flows driven by lease contracts. - If we discount cash flows at 10% today, with the ten year hovering at 2.2, would we still use 10% if the ten year went to 6% in a few years? Or would we require a larger spread.

- If we use historical total return CAGR’s are we ignoring the starting point (I’m asking). So many, including Arnott and Asness, that we are looking at ERP of 2-3% going forward based on current valuation levels…now they’ve been saying it for years and are so far wrong, but what if? Trailing P/E and CAPE P/E’s are high. You mentioned in your paper that growth rates are probably going to be lower going forward, so why use the historical rate and not incorporate that estimate.

Erik’s Reply

Thanks so much for your comments! I really appreciate your thoughts and have broken my responses up by bullet point below.

Discount Rates for REITs

Your point about REITs is a good one and I need to do some more thinking about that. As I was writing this essay, I realized that my thinking on the discount rate I used for Realty Income O was not compatible with the way I was thinking about it in this essay. In a sense, a REIT is a hybrid investment – essentially a real estate mutual fund – and most REITs are set up for growth through acquisition. The real estate part of this instrument represents, I believe, a bond-like risk; the expansionary aspect of this instrument represents an equity-like risk. It’s hard for me to resolve those two… I need to keep thinking about that.

Changing Interest Rates

Regarding your second point about changing interest rates, I have two responses.

First, I got into a discussion with an economics professor a few years ago who had essentially the same take. My counter-argument to him was that if you boosted the discount rate when bonds were high (he used the extreme point of bond yields in the Volker years), you would essentially be discounting the perpetuity of the company’s cash flows at a higher rate.

The professor acknowledged that discounting at a high rate in perpetuity was inappropriate, so walked back his contention. He said that one should do a multi stage model with a high discount rate in the short-term which would gradually revert to a long-term historical rate as time when on.

I ran a few experiments with this multi-stage discount framework and in fact, the difference to FV was something on the order of 5%-10%. Considering the great uncertainties when valuing a company, I consider 5%-10% to be a rounding error when it comes to valuation.

Second, after thinking about this vector vs. scalar issue, I would, in fact say that a 6% yield on a government bond is completely separate from a discount rate on an equity, so I would not advocate any change in equity discount rate methodology because of a change in government discount rates.

What I do see is that if government bonds are paying 6% and let’s say high quality corporates are paying 8%-9%, an asset allocation that is heavy toward bonds looks a lot more attractive than one that is heavy toward equities.

A few comments on this approach:

- I understand that the yield is a nominal one, so real yields may be no higher or not much higher than today. However, in a well-managed monetary system, inflation should mainly relate to population growth and resource scarcity, so the “natural” inflation rate should be low. Government policy sometimes boosts this in the short-term (e.g., Volker era), but that condition does not persist perpetually. I’d say if you start being able to get a nominal yield nearing 10% on the bet that a government or a company won’t fail and you can get a duration on that bond of something like 20-30 years, over most of the life of the bond, you will be generating very strong real returns, even if the initiation of investment has only a slight nominal yield.

- If most market participants are using a conceptual framework of “start with the fixed income rate and add a risk premium” for discounting equity, many equities will be discounted at a higher rate than I would use over a long term. As such, their valuations might be very attractive in relation to their market prices in such a case. As such, I think that I might find some really attractive upside risk opportunities in that environment, and I’d have to balance my desire for a secure bet on non-failure (i.e., bonds) with my greed for a bet on relative success (i.e., attractively-priced equities).

Expected Returns When Market is Overvalued

Regarding your third point, regarding the starting point for an investment in the market, this is really an appropriate thing to ask and I’ve been thinking a lot about it recently.

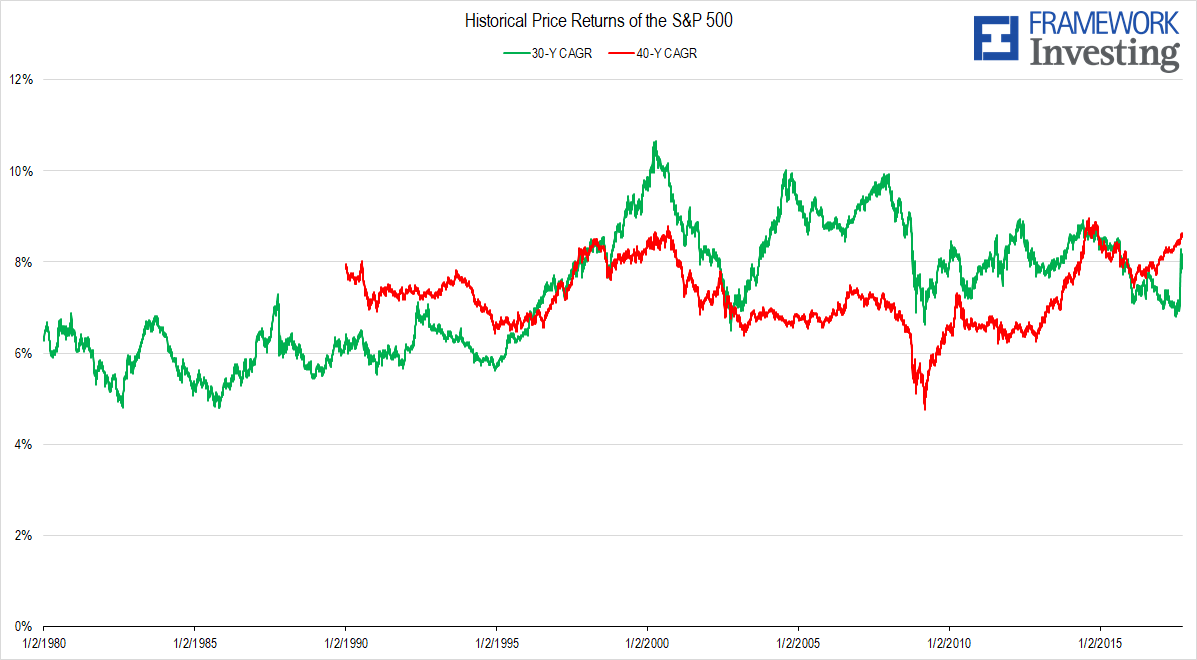

Looking back at that returns chart in the piece, I noticed that while the shorter-run CAGRs did not look too high, the longer-run CAGRs – 30-year and 40-year – do when compared with previous maxima.

Figure 1. Source: YCharts, Framework Investing Analysis

If you think about a 40-year CAGR, it is essentially the investing life of a working person – 25 years old to 65 years old. The present 40-year CAGR is sitting at 8.6% and there are only two periods where this has been higher – 2000 and 2007. So if you ask the question “Would someone investing today with a 40-year time horizon do well to invest in stocks?” to me, the answer looks like a “no”, assuming these returns mean revert and especially considering the extent to which there are likely headwinds moving forward.

(By the way, the maximum 40-year CAGR is measured from a low point in the ’74 bear market. The second highest 40-year CAGR – recorded in 2000 – was measured from 1960 and the prior 10 years had been very good thanks to the post-war boom).

If the market’s price is relatively high – in other words, the prior returns have been fairly strong – many stocks in the index should have a relatively high price-to-value ratio.

If I discount at a 10% rate I am saying that I demand a 10% return no matter where we are in relation to long-term returns. Because I am demanding a high return I should find relatively few bargains and will not invest. If I do find a company that looks undervalued at this discount rate, I should make sure I’m right and invest! If I’m right about the valuation drivers underlying the company, then even if the price falls, I still accept little valuation risk and can add to the position when the stock price is lower.

You’re right: I probably should use a lower rate considering my view on growth. That said, maybe I’ll be wrong – a lot of things happen that I don’t expect – so I am happy to continue to retain my relatively strict requirements for returns and can at least point to an historical number.

It’s worth pointing out that I think that the historical number has a basis in the real economy. I refer to several papers in my article that support this idea, so the historical rate I am using has some basis in a real effect, I believe.