Analysts have issued bearish reports regarding General Electric GE over the past few weeks. They offer two main complaints about the firm:

- Now that GE has sold off the consumer finance business, the industrial business will not be generating very much cash (there may even have to be a dividend cut, opined one analyst).

- The firm has huge unfunded pension liabilities that will bring the company to ruin.

Let’s look through each of these contentions one-by-one.

Cash Flow “Shortfall”

GE publishes a figure that it calls Industrial CFOA – Cash Flow from Operating Activities for the Industrials business. This number excludes the dividend that GE Capital pays to GE’s industrials business, so offers a “pure” view of the cash generated by this segment.

Luckily, the firm also provides segment-level cash flow statements for both the industrials business and the financing business, so we can estimate our preferred cash-based profit metric – Owners’ Cash Profits (OCP) – for the Industrials segment separately.

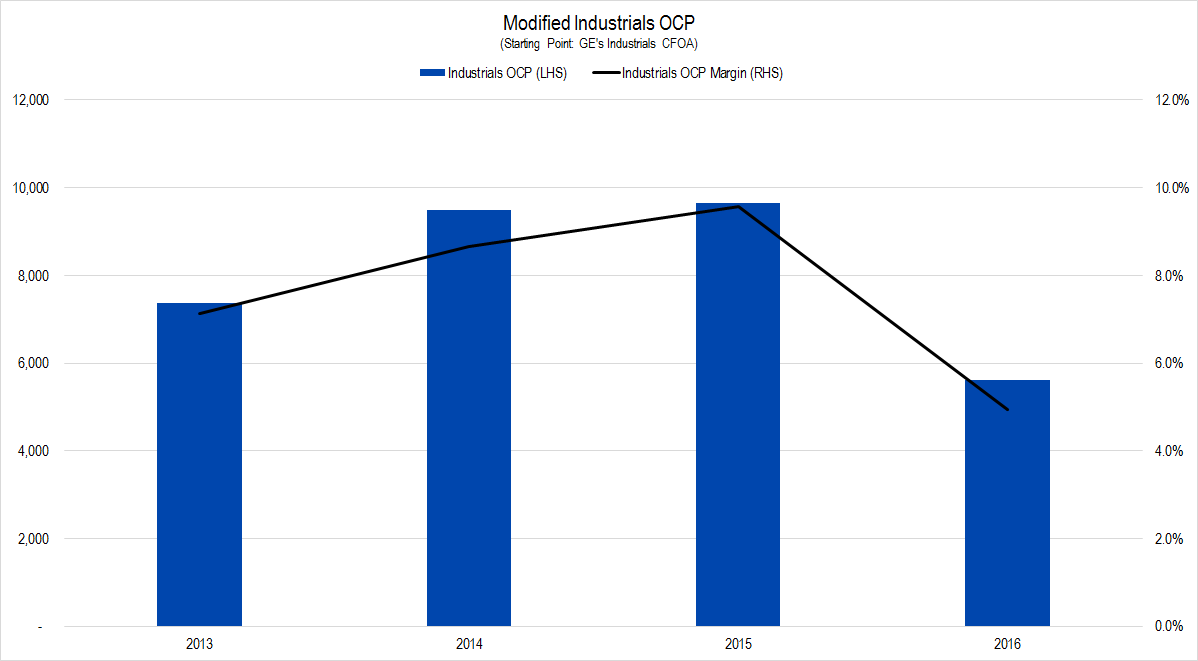

Graphing out Industrials’ OCP and OCP margin over the last few years looks like this.

Figure 1. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

Note that 2016 saw the firm paying $1.4 billion in taxes related to a sold business and $350 million in pension plan funding that company management would like analysts to add back into the Industrials CFOA number (since it is “extraordinary” in accounting terms). I have not added these figures back in the above calculation.

This leaves us with an average OCP margin of 7.6% during this period – which is the only period over which we can be confident we are comparing apples to apples due to the divestitures.

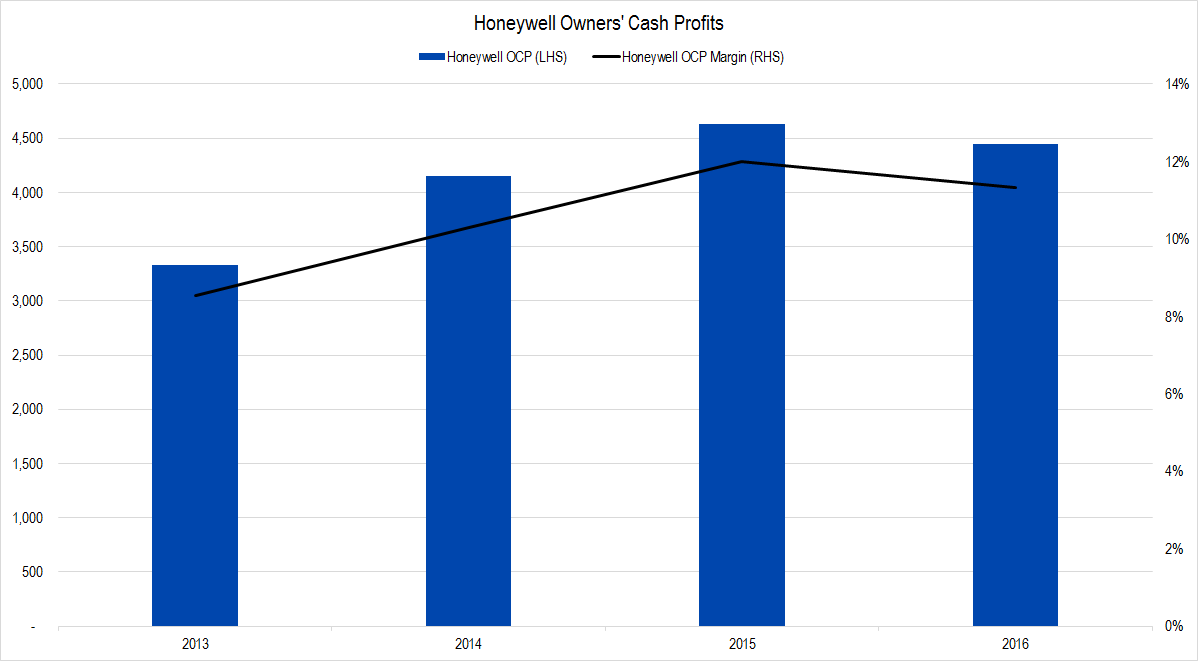

Compared to industrials competitor Honeywell, GE’s Industrials segment OCP does seem light – by about 40%.

Figure 2. Source: YCharts, Framework Investing Analysis (Avg. OCP margin = 10.5%)

That said, while GE is kind enough to spoon feed us the Industrial CFOA data, the Industrials business works in conjunction with the Financing business in each of the Industrials verticals; GE is a company, so it doesn’t make sense to say that some of its cash flows don’t “count.”

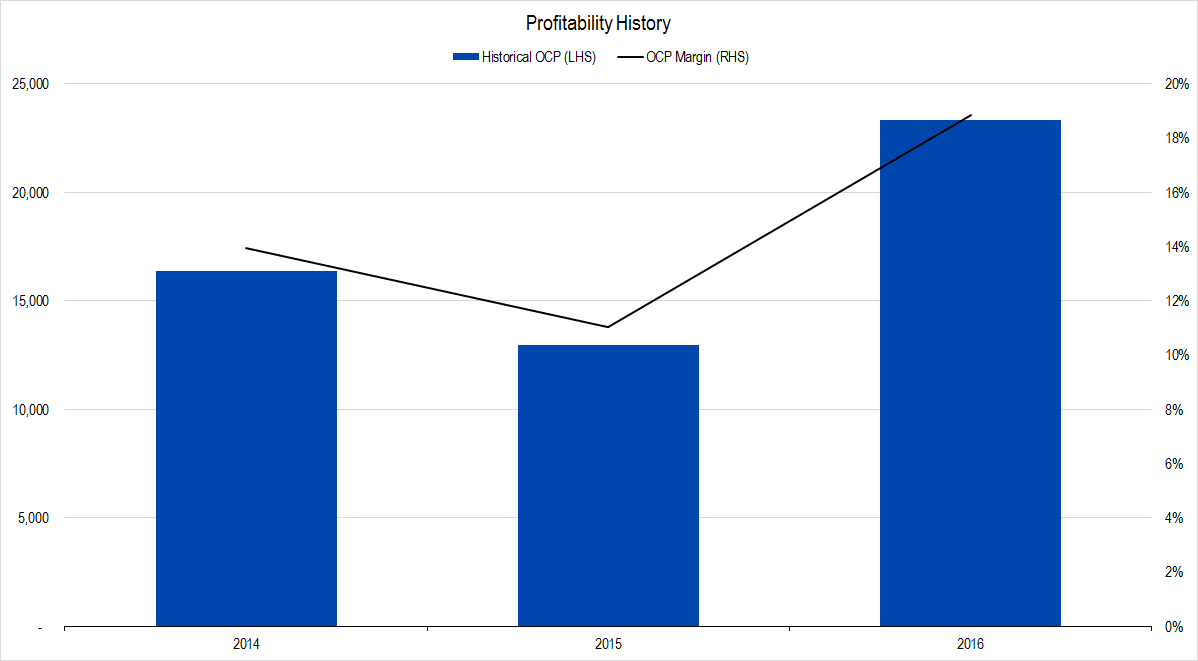

If we look at GE’s overall OCP – including the Financing business but not including the divested businesses, the chart looks much more respectable.

Figure 3. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis. (Avg. OCP Margin = 14.6%)

(Notice that I only included three years in this view rather than four, as in the previous. The reason is that the company does not provide 2013 cash from operations provided by the financing businesses that were discontinued during 2016, whereas these data are provided for the Industrials segment.)

Looked at as a single entity, GE’s OCP margins are around 50% higher than those of Honeywell on average if 2016 results are included, and around 20% above those of its competitor if we disregard 2016 as an outlier.

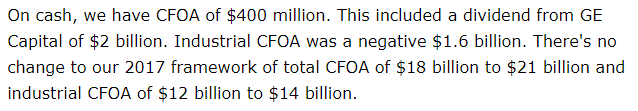

First quarter cash flows were weak at GE, but any single quarter in a year can be weak for any number of non-economic reasons. For investors in GE, the important thing was that the company’s management guided to between $18 and $21 billion in company-wide CFOA for the full-year 2017. If we assume that roughly $5 billion of that is set aside for maintenance capital expenditures (roughly what Total Depreciation and Amortization has been over the past few years), 2017 OCP should be in the $13 – $16 billion range – roughly in line with the years 2014 and 2015.

Figure 4. Source: SeekingAlpha Transcripts

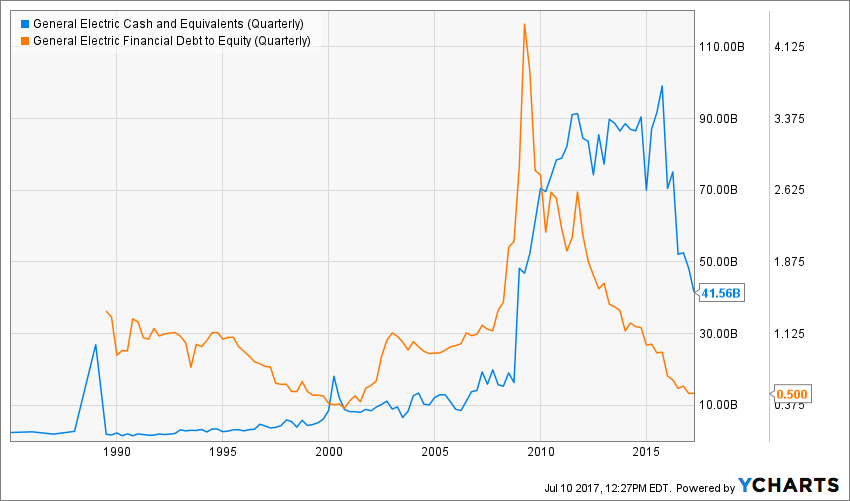

This cash flow is ample to pay the roughly $9 billion in annual dividends the firm has been paying out lately – even in the worst-case profitability scenario. The company has also announced that it plans to buy back from $11 – $13 billion in shares this year, bringing its total shares outstanding down to just over the 8 billion level. For this, the company has nearly $42 billion in cash and another $42 billion in liquid investments. Before the 2008 crisis, the company generally kept around $15 billion in cash on its books, and now that its designation as a SIFI (Systematically Important Financial Institution) has been removed, it does not need to park as much cash on its balance sheet any longer.

Figure 5

From this analysis, I see no reason for sell-side analysts or investors to worry that GE will experience some sort of cash flow shortfall in the near term, and certainly, there is not, in my opinion, any basis for forecasting that the firm will be forced to cut its per-share dividend payment.

Pension Apocalypse

The first thing I would note about pension funding is that it is something like a mortgage. It is an extremely long-lived liability that typically exceeds income by a wide margin.

If you have a $300,000 mortgage, are you worried that you are going to go bankrupt because your pre-tax income is only $100,000 a year? While not perfectly congruent, GE’s pension shortfall is the same sort of a “problem.” The firm spends around $400 million in cash each quarter to service its pension liabilities, and from our analysis above, it’s clear GE is generating more than enough cash to pay this charge. If the pension were fully funded, would shareholders enjoy access to greater profits? Yes. Should you be worried because it holds an unfunded pension liability? Probably not much.

From a common-sense perspective, this is the story in a nutshell. However, if you’re in the publishing business, you need to garner attention. Bloomberg published a long story about GE’s pension liabilities, filled with worrisome quotes from business school professors and an argument based on two observations:

- The pension shortfall is huge – the biggest in the S&P 500.

- GE has spent money on buybacks that might have gone to “fill the pension hole.”

Regarding the size of the shortfall, less than one minute on a financial data screening tool like YCharts should be enough to convince you that it’s reasonable that GE’s pension shortfall is one of the largest in the S&P 500 for the simple reason that it’s one of the largest firms in the S&P 500 and one of only a fraction that offer pensions at all. GE is 13th largest in terms of market capitalization and 12th largest in terms of number of employees; there are only three firms with larger market capitalizations to even offer pensions and those with more employees tend to be retailers – companies that traditionally offered much less generous compensation packages.

Bloomberg’s writer also tries to stir up emotions by saying that GE should have used money that it spent on buybacks to fund its pension shortfall. It points out that Nelson Peltz’s activist Trian Fund took a stake in GE in 2015, and afterwards, GE’s CEO, Immelt, began to increase buybacks – $45 billion in buybacks over 2015-2016.

This contention amounts to the financial equivalent of fake news. 2015-2016 were the years that GE had taken the step of spinning off what remained of its GE Capital business. The company’s stated plan at the time was to sell off the consumer finance business and use the proceeds to buy back shares. If the firm did not do this, it would have effectively diluted the earnings of all the shareholders to the tune of $45 billion. This would not only have hurt Nelson Peltz, it would have also hurt the GE Pension Fund, which is a large holder of GE shares.

Investment Strategy

GE has undergone many changes in the past few years and its financial statements are not easy to work through.

We are redoing our GE analysis from the ground up and will be issuing investment strategies to our Framework Investing members over the next few days. For now, we can say that the concerns raised in sell-side reports and in the media about GE’s supposed cash flow shortfall and deep pension hole are unfounded.