A few weeks ago, I published an analysis of Netflix revenues and medium-term cash flow growth. By the end of the second article, I was convinced that no one on earth knows what Netflix is worth, so my last article in this series has been slow in coming.

That said, the topic of this article is an important one — off-balance sheet obligations — and is a consistent talking point for Netflix bears.

Even though some readers’ eyes may begin to glass over when they see the words “off-balance sheet”, the topic is easy to understand and important to understand in certain circumstances.

The balance sheet shows the store of the company’s assets, which have been acquired using either debt or equity. As our mini-course on the Language of Business points out, the reason that a balance sheet is so called is because the assets must balance with the combined debt and equity.

An obligation would be classified as a liability, so let’s look at the section of Netflix’s balance sheet showing liabilities.

Figure 1. Source: Company Statements

“Current liabilities” means the ones that must be paid for in the next year; Netflix owed $5.5 billion of those at the end of 2017. The long-term obligations total just under $10.0 billion, to add up to total liabilities of $15.4 billion.

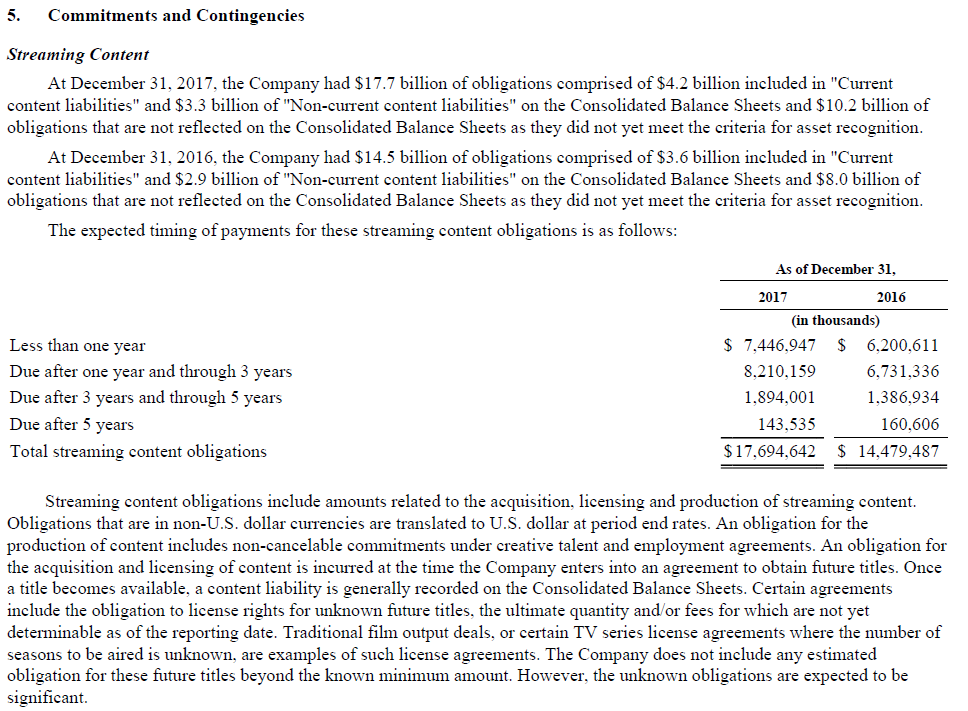

However, looking more closely through the notes to the financial statements, I found the following table.

Figure 2. Source: Company Statements

Contingencies associated with streaming content that are current (i.e., due in less than one year) total, according to this table $7.4 billion — nearly two billion more than all current liabilities listed on the balance sheet. In addition, streaming content obligations with maturities from now through forever total $17.7 billion — again higher than all of Netflix balance sheet liabilities.

Some value-oriented (and balance sheet oriented) value investors worry a great deal about these off-balance sheet obligations. Here’s a representative Twitter post from one of them:

Figure 3. Source: Twitter

Netflix’s streaming obligations are not counted on the balance sheet for reasons to do with the accounting rules. The obligations are real, but not quantifiable yet because they relate to movies that have not yet been released or even made in some circumstances.

These liabilities do seem worrisome, but are they?

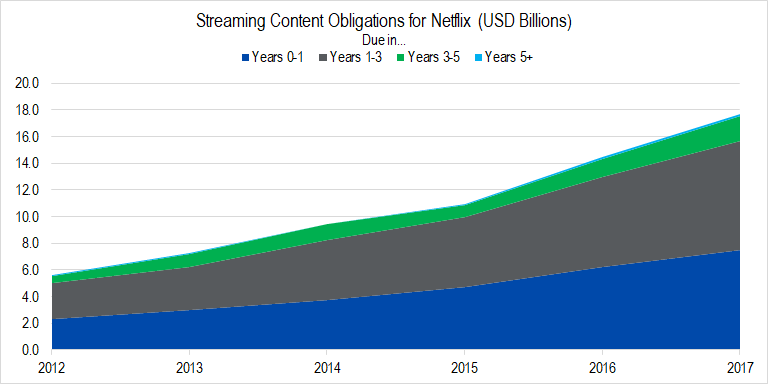

The first thing I did to try to assess the impact of these obligations was to go back and pull the numbers since Netflix began its streaming service in 2012.

Figure 4. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

Streaming obligations increased by about 3x since the start of the streaming service — a large pick-up.

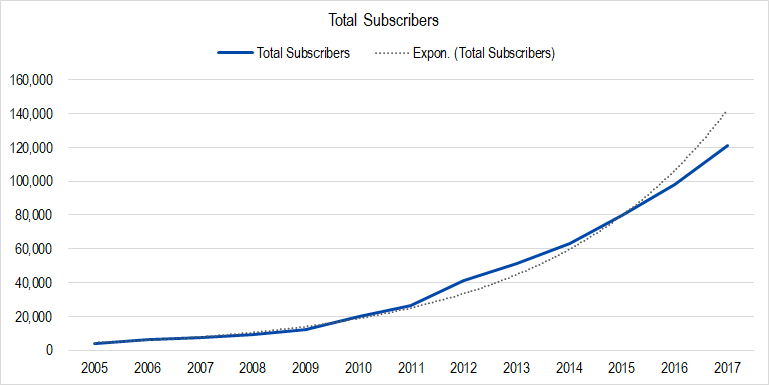

However, even as I was looking at this, I was remembering back to the very robust subscriber growth for the firm over this time as well.

Figure 5. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

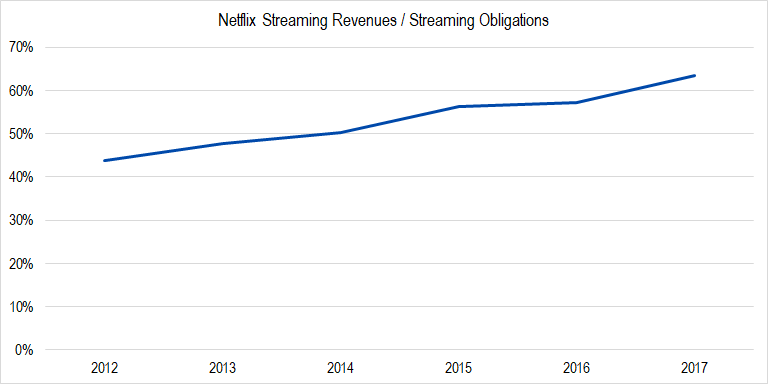

When I looked at revenues compared to streaming obligations, I found something interesting:

Figure 6. Source: Company Statements, Framework Investing Analysis

The line is upward-sloping, meaning that revenues are growing faster than the obligations are accruing. That’s a good sign.

In our daily lives, we are used to borrowing more than we are taking in. Think about the relationship of one’s home mortgage to one’s gross salary. Usually, the former is some multiple of the latter. This is essentially the situation at Netflix at present. Netflix’s “mortgage” started off being worth 2.3x its “gross salary” — now, because of a lot of raises, it is only worth 1.6x its salary.

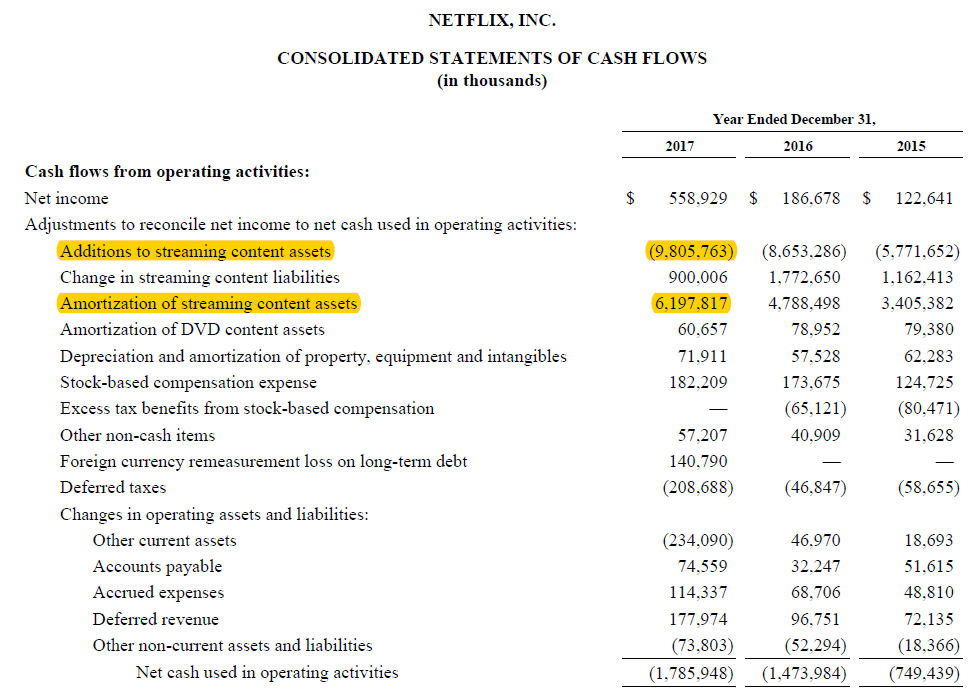

We can see how this plays out on the statement of cash flows as well.

Figure 7. Source: Company Statements

The “Additions to streaming content assets” is the cash the firm actually spent to acquire rights to streaming content. The “Amortization of streaming content assets” is the non-cash charge the company took as the content was consumed by its clients.

As an investor focused on cash flows, I was happy to see the Additions line item included in operating cash flows. The big cash outflow makes operating cash flow look worse, but it is certainly a necessary part of Netflix’s operations, so I was glad not to see it in the Investing portion of the Statement of Cash flows.

What this tells me is that the company is growing quickly and spending cash to acquire more and more varied content. Just as a firm early on in its growth cycle should be. Netflix bulls implicitly believe that, at some point, the ratio of revenues to obligations shown in Figure 6 is going to increase to 100% and above; as that balance shifts, the firm will be much more profitable. Eventually, the cash inflows from the Amortization of content will more than offset the outflows from the Additions line in Figure 7 and cash flow from operations will turn positive, they believe.

Netflix bears worry that at some point, Netflix will face competition that creates a revenue shock or that its revenue growth simply slows such that the line in Figure 6 ceases to increase.

As I mentioned in the article analyzing medium-term growth rates, it is very hard for me to see which of the two cases are more likely. Certainly, either are possible.

The one thing that I think is silly to worry about is that Netflix is attempting to hide some huge future obligation and that its balance sheet is much weaker than it is.

Conclusion

As I said before, Netflix future growth is so unpredictable, I do not have confidence that one or the other of the valuation scenarios is more likely, and the average value of all our valuation cases is just in the middle of the valuation range.

Does this mean that an investor should not invest in Netflix? No — of course not! If you hold an index fund in your portfolio, you already own Netflix, and some portion of the returns you enjoy are based on Netflix’s amazing performance.

For those of you who are itching to take a direct position in Netflix, I think the best strategy is to limit your exposure through position sizing. If Netflix soars another 60% over the next year, you’ll be kicking me, but if it falls by half, you’ll be thanking me. From a valuation perspective, playing over / under with Netflix is as good as tossing a coin.