For General Electric and our analysis of the company, this has been a painful week after a painful few months. It is hard to describe my shock at GE’s very weak third quarter cash flow results, and the fact that the firm announced on Monday that it would cut the dividend — something that I thought was improbable a short time ago — added insult to injury.

This is the second time in my career that I have been materially surprised by a result — the first time was with a NOR flash manufacturer that had been spun out of Advanced Micro Devices, Spansion — and the very first time when a significant (and levered) proportion of my own portfolio and the portfolios of my family and friends was at risk. For those of you who trusted my analysis of this investment — for I consider those reading this to be my friends — I humbly apologize.

I have not taken any action on my portfolio or those that I control. I do not want to make a knee-jerk reaction on an emotional basis, but rather to improve my understanding of GE’s prospects. Today’s price may be too low, but without that better understanding of the underlying value, I can only think that any action I might take would be an X-System speculation rather than a reasoned C-System decision.

So, how do we take where we are and make the most of? Over the last two and a half days, I’ve done two things — first, I’ve gone through Monday’s Investor Day transcript and compared it to prior conference call transcripts and combed through the financial statements and websites attempting to triangulate information and get a better understanding of the company. Second, I’ve thought about the process that I took to value GE and considered where that process came up short in this instance. This article delves into what I’ve found in both areas.

Process

Everyone makes mental models to make the job of analyzing a complex system or situation easier. My mental model for GE is that it is a company that sells goods and services that are necessary for the advancement of the human race.

My model for the demand environment, then, revolves around the needs of a growing, aging, developing world: power, medical care, transportation. This is a company that should grow at about the pace of economic growth in the countries in which it operates, which, with GE, is basically all of them.

The company has been undergoing a lot of changes in its portfolio — divestments and acquisitions of businesses — so just looking at the revenue numbers to try to gauge the strength of the underlying demand is difficult.

My response has been to try to isolate certain businesses — GE’s industrial segments, in particular — and look at their year-over-year change with an eye for corporate actions such as acquisitions or divestitures. I’ve also looked at reported backlog and order volume as I expected to see weakness there before a weakness was reported in revenues.

Since starting to invest in the company in 2015, I have checked these measures against my mental model, and each time, they seemed to jibe pretty well. I became more convinced that my mental model was correct the more times this occurred.

Analyzing profits was also difficult due to corporate actions and reporting factors. Because the company splits out prior period segment data in a different way and buys and sells businesses, I am cautious about comparing results in the distant past to more recent ones. As I discussed in our GE presentation a few months ago, I try to triangulate between competitor results, profitability on an accounting basis, and what I see on an OCP basis.

Again, since 2015, I have checked my analysis against actual results and each time, they seemed to jibe well with my expectations. Until they didn’t — which is what left me speechless after the third quarter earnings announcement.

Analyzing investment level was also difficult due to the dispositions. I could see how much the firm was spending on capital improvements, but in most cases, that number was swamped by an even larger cash inflow due to disposals. I had a mental model for the level of investments the firm was making, but because the disposition inflow was so large, I discounted the information content of the net number.

Here are the areas of the analysis that should be sharpened:

First, in terms of demand environment, I am reminded by this experience that underlying every year-over-year percentage increase, there must be multiple individual customer decisions driving discreet transactions. In the section below, I will detail what I think happened on a transaction level that I missed by looking at the company from a big-picture level.

Second, with regard to the profit numbers, because there was a lot of noise in the system, I thought that there were some things that I simply wouldn’t be able to know until the corporate activity had cleared out. Additionally, I bought into GE management’s talk of the financing arm paying a dividend to the Industrials business without enough suspicion. In my summer valuation, I finally got frustrated with the management line and recast the numbers myself, but this process should have started earlier.

Third, I did not ask enough questions about the investment level and efficacy. The large dispositions made it very hard to track these points, especially efficacy and because the results I was seeing generally agreed with what I expected to happen (i.e., dispose of the financial assets and plow that money back into the industrial businesses), I did not look further.

In a phrase, I didn’t question the effects of GE’s business portfolio changes enough. I checked actual results against my expectations, but when those figures agreed, I did not take the next step and say “What might go wrong from here?” I looked at results and essentially said “Looks like I’m right — let’s move onto something else.”

Company Details

Realizing that my approach had been too big-picture regarding GE, I have taken a lot of time to dig into the business that experienced the biggest surprise — Power. There are other contributing factors (especially Oil & Gas) that exacerbated the abysmal third quarter numbers, but a great deal of the blame lies with my old friends in the Gas Turbine division — exactly the business segment that JP Morgan analyst Steve Tusa called out.

I will be doing more research on this over the following days and weeks, but here are some of the details that, while available ahead of time, I missed by taking my high-level approach.

Geographical Concentration

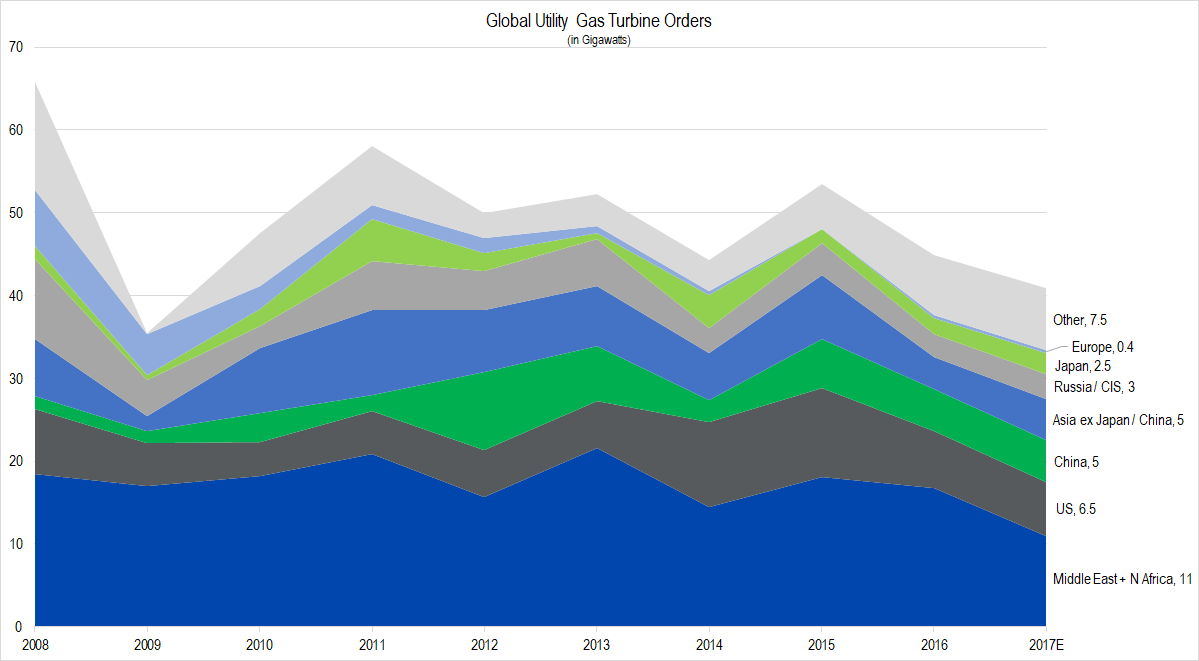

The gas turbines that GE produces mainly (roughly three-fourths) are sold to electric power utilities worldwide. But the distribution of utilities is not uniform.

Source: McCoy and estimates from JP Morgan for 2017

The first thing to notice is the light-blue Europe region barely visible second from the top. Notice that Europe starts out as a geography with sizable orders in 2008 (6.8 GW, tied for third with Asia ex-China / Japan). By the end of this series, gas turbine orders are barely measurable and have recorded a zero year as well.

This represents the ultimate bear case for the gas turbine business — gas is completely replaced by renewable sources. I don’t think this bear case should be extrapolated, however, because there are historical (nukes in France, etc.) and geopolitical (Germany wants independence from Russian gas) reasons why Europe has weaned itself off gas, and it should be pointed out that Germany and many areas in central and eastern Europe have large coal-fired utilities. I don’t think it should be extrapolated, but I am planning to go back and research this more.

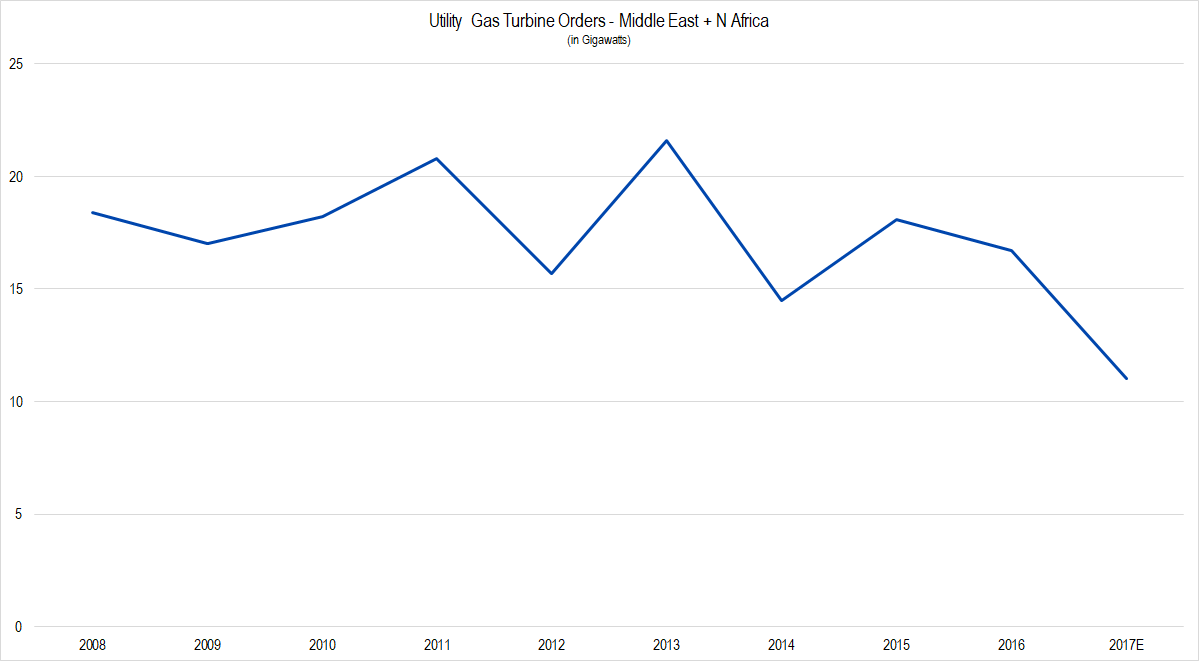

The second thing to notice is that deep blue sea on the bottom of the graph representing the Middle East and North Africa. Let’s look at just orders those orders separately.

Source: McCoy and JP Morgan estimates for 2017

Two things catch my eye about this – first, this is a short data series, so I don’t want to make too much out of this, but there seems to be more volatility over the last six years than in the first four. Second is the notable forecasted drop-off in 2017. In 2016, GE Power derived about a fifth of its revenues from the Middle East, so a drop as severe as this (33%) would have a material impact on revenue generation.

The last thing to note in terms of geographical concentration is that the Middle East and the US represent an average of 49% of global orders over the 2008-2017 period. This is the real take-home point: demand for gas turbines might grow along with the growth in global population (as in my mental model), but not only will the growth be lumpy (as I acknowledged), it is also concentrated in two specific geographical areas that are subject to very real political constraints.

Meet the newest subscriber to Utilities Middle East magazine.

There are some other Middle Eastern tie-ups that I have found, but I’ll leave them for a later article after I have had more time to research. Put simply, GE’s exposure to the Energy space is higher than I had thought due to highly market-specific secondary effects.

Product Cycle Issues

I won’t go into great detail about this, but where GE’s new turbine business is in its product cycle contributed to the surprise in Power. GE came late to the game of manufacturing very large H-Class gas turbines. The company’s technology is very good, so it now has a market-leading share, but the company had to scramble to design, test, and market these large, expensive devices.

Early in the release cycle of a new product, revenues increase quickly, but profits and cash flows tend to lag. Depreciation on equipment is high compared to revenues, cash flows out to buy inventories, and engineers are working hard to iron out kinks as the products go to market.

The slow-down in orders shown in the graphs above occurred early in the life of its new HA turbine product line. If the slow-down occurred after the product was more mature, the negative effects of operational leverage would certainly have been less. As it is, they were exacerbated.

Service Issues

This is a topic that I still need to delve into in more detail, so I will cover it only briefly here.

The crown jewel of GE’s Power business is not its big gleaming turbines. Instead, it is its gleamingly profitable service business. There are essentially two classes of service: AGP refurbishments and transactional repairs.

AGP (Advanced Gas Path) is a method of refitting legacy turbines with new hardware so that the generative efficiency of the turbine is increased. There is a parts component as well as a large service component, since the new parts must be installed on idled turbines. GE has been selling AGP very hard and built up a large amount of inventory for the expected order flow that never came. The company ended up with a cash outflow of $2 billion rather than what they had expected, a cash inflow of $3 billion. That is a big difference. AGP revenues were down by 54% during the third quarter of 2017 versus the third quarter of 2016, and this looks like the main reason for the truly abysmal profitability and cash flow in the Power segment.

In addition to the AGP shortfall, Power services was relying more and more on short-cycle repair contracts to make profit targets, but for some reasons related to poor execution, it was not able to pull that together this year. Revenues from this high-profit service were down 18% year-over-year.

In total, these issues contributed to a perfect storm of weak profitability and cash flow. The real issue in determining a fair value range for GE is understanding which of these are structural, which are cyclical, and how soon will the conditions reverse themselves.

Conclusion

While this counts as my second material negative surprise as an analyst, I think that, in the end, these learnings strengthen both my analyses going forward and the Framework service overall. It is impossible to bat 1000, as any major leaguer knows. So here is how I and Framework will use this experience to improve:

First, we have brought on additional analyst resources to allow me to focus in greater detail on specific analyses and educational offerings.

As much as I talk about structural factors, I must admit that they probably play a part in my failure to correctly assess GE’s short-term business environment.

Framework is a subscription service, and anyone publishing on a subscription basis must make sure that they publish articles that attract and hold reader attention. Sometimes it is hard to tell what will click with a certain reader or type of reader, so my approach has been to publish as often and as voluminously as possible. Also, I worry that if I only write about one or two companies, I’ll become known as “The guy who analyzes Oracle” or “The guy who analyzes GE,” which I imagine would limit the attractiveness of a subscription offering.

I want my attention focused on playing an A game in terms of valuation and portfolio management. To that end, teaching our model to additional analyst resources to ensure we meet the needs and demand of you, our members, is an important step.

Also, while I think the shorter overview pieces like the “Five-Minute Valuations” are important in that they reinforce the simplicity of the cash flow generation / valuation process, I also want to delve more deeply into and publish more about the companies on which we do screening valuations. The analyst and I worked on Nike NKE together and are working on Starbuck’s SBUX right now; you can expect to see more detailed work for these companies in addition to the overview material.

Third, I have realized that I am most attracted to companies in transition as I think they are the most likely to be misunderstood by market participants. While these companies can provide excellent opportunities (e.g., Oracle’s transition to the Cloud, IBM’s transition away from consulting), I think that I have probably discounted the great uncertainties that usually accompany big transitions. I’ve resolved to approach transitions with more circumspection and an appreciation for the difficulties involved.

Last, after spending a career in the investment business, I think that I am perhaps too jaded about the motives of participants in the Investing-Industrial Complex — especially sell-side analysts. A read through JP Morgan’s Tusa’s report on GE shows a great depth of understanding about the Power business and about cultural issues within the firm. I believe that principal investors — who are less constrained by the time horizon issues faced by professional analyst agents — have a natural advantage in investing, stemming from the luxury of being able to take a longer term view on valuation. That said, a sell-side analyst’s focus on a particular industry and a long background with a company and its management, competitors, and clients sometimes offer important insights into fundamental drivers of value. I have resolved to look for reasons to pay attention to a sell-sider’s analysis rather than reasons to discount it.

I will be publishing more on GE, including a new valuation range, once my analysis is finished.