It’s a scientifically proven fact: we are terrible at forecasting the future.

Our tendency is to anchor on present conditions and assume that the future will be about the same as now. What’s more, we are happy to disregard historical evidence regarding how much change has occurred in the recent past.

This tendency, termed the “End of History Illusion” by the social psychologists that discovered it, has big implications for investors. A recent article on a site for financial advisors entitled The End Of History Illusion And The Problem With Goals-Based Investing, explores one manifestation of that illusion. Namely, investors may not be allocating capital in a way that will meet their future needs, but rather as an extension of their present desires.

Working as a hedge fund and third-party research analyst, I have seen firsthand another manifestation of this behavioral bias, which I believe is inextricably tied to the tendency for financial markets to go through cycles of booms and busts. When times are good and the market is enjoying a strong upswing, and when times are bad and the market is crashing, we have a difficult time envisioning either of these states changing in the future, despite plenty of historical evidence to the contrary.

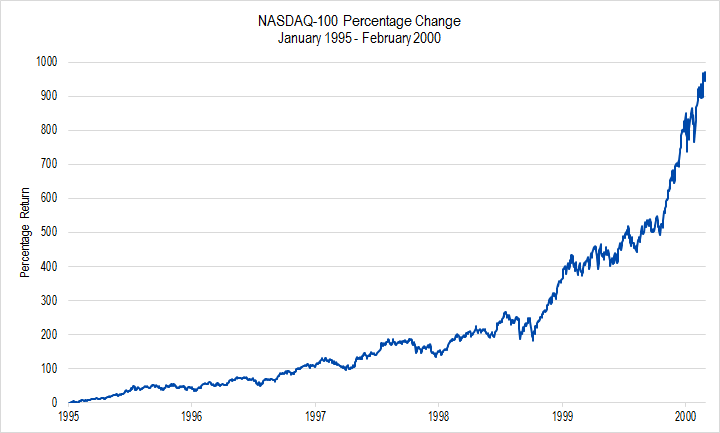

Think back to the Tech Boom of the late-1990s. The Internet was changing the way people communicated and businesses operated. A stock that IPO’d at $10 per share would close its first day of trading for $23 even if the firm was barely generating revenues, let alone profits. Even an index investor could easily generate a 20% return year after year, so why not mortgage your house or max out your credit cards to get some extra cash to play the markets? If the future was going to be essentially the same as the present, it would be silly not to!

Source: YCharts

In contrast, think back to the depths of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis. Even one of the most conservative and liquid financial instruments available to investors – the money market mutual fund – was trading for a few cents less than face value, so why not pull your money out of risky assets like stocks? If the future was going to be essentially the same as the present, it would be imprudent not to!

Of course we know that both of these cases eventually “normalized,” and when they did, investors who were under the End of History Illusion suddenly found themselves out in the cold. In the Tech Boom, it was a sin of commission – people were invested when they shouldn’t have been; in the Financial Crisis, it was a sin of omission – people weren’t invested when they should have been.

The only way not to fall prey to this manifestation of the End of History Illusion is by having a firm understanding of how a company creates value and a repeatable framework for assessing value that does not hinge upon current “multiples” or other transient valuation proxies. Much of a company’s value is related to how fast its cash flows will grow in the future, so a sound valuation framework also helps an investor rationally and transparently assess likely future growth in the context of historical evidence and observable criteria.

If you can’t tell that your valuation implies that the company in which you are invested will expand longer and faster than any company in the history of the world, or that your valuation implies that the company’s cash flows will shrink at 10% per year ad infinitum, your “investment” may be only pure speculation.

The End of History Illusion, Jordi Quoidbach, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Timothy D. Wilson, Science, January 2013: Vol. 339, Issue 6115, pp. 96-98