Last Friday, Goldman Sachs – nicknamed “The Vampire Squid” by journalist Matt Taibbi – issued an industry report with opinion changes on several solar power companies. An IOI member – a retired solar power executive who owns a significant stake in one of Goldman’s downgraded firms – called me to try to make sense of the analyst’s change of opinion and to frame the valuation arguments the analyst was making.

It turns out that there is a lot to unpack in this downgrade announcement – with lessons regarding the structure of the investment banking business, the behavioral biases that influence even experienced analysts, and shortcomings in the way a lot of investors – “pros” included – value companies.

This article will focus on the structural and behavioral issues, then we’ll dig into the valuation issues in a follow-up.

The Effect of an Analyst Change of Opinion

One glance at the chart below illustrates how influential an opinion change from a major investment bank can be. $220 million of First Solar’s (FSLR) market capitalization disappeared in one day on the basis of three words: “FSLR to Neutral.”

Figure 1. Goldman Sachs’ analyst, Brian Lee (like me, a Morningstar alum) downgraded First Solar (FSLR) to Neutral from Buy, Vivint Solar (VSLR) from Sell to Neutral, and SolarEdge Technologies (SEDG) from Neutral to Sell. One stock, SunRun (RUN) was upgraded to Buy.

Such an extreme move in stocks on the basis of an investment bank (or “sell-side”) research report is par for the course. Sell-side research analysts sit at the pinnacle of the “Investing-Industrial Complex” and are the quintessential example of Fundamental analysts described in my Forbes article The Three Great Investing Fantasies: Technical, Ratio, and Fundamental Analysis. The research analyst is highly trained, well-compensated, and has near insider-level information about the company from his frequent meetings with the upper management team.

It is absolutely understandable that the market would react to this analyst’s change of opinion. Investors believe that this analyst – whose title is ‘Vice President’ at the most powerful investment bank in the world – has an excellent understanding of the company and is working hard to serve his bank’s clients by providing excellent investment advice.

Please allow me to disabuse you of this impression.

Wall Street Analysts Are Not Concerned with Providing Excellent Investment Advice

Even if you’re the best client of an investment bank’s private wealth management division, the bank’s research analyst doesn’t work for you, nor does he care if you make money or not.

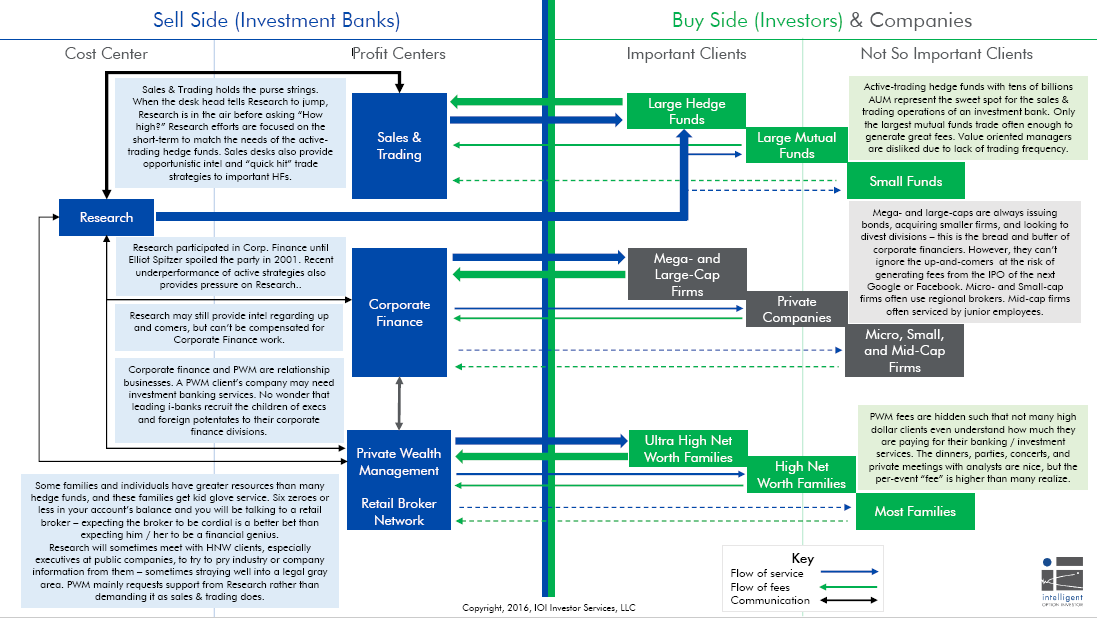

An analyst’s focus is simply not providing investment advice. Instead, the sole job of any sell-side research analyst is to provide as many plausible reasons why institutional investors should immediately transact in the stocks he or she covers. The research analyst’s real boss is not the head of research, but the head of sales (see also the infographic below and download a copy of the PDF here).

Figure 2. Simplified view of the “Investing-Industrial Complex”

Research is an expensive business and the only way to cover the expense nowadays is to create transaction flow through the bank’s sales and trading desks. Much of the focus at banks has shifted to keeping a short list of about five large, frenetically trading hedge funds happy. These “focus firm” clients end up footing the bill for research through their large, almost continual order flow.

The only sin that a research analyst can commit is doing something that angers a large client enough that the client puts the sales desk “in the penalty box.” The only way for an analyst to succeed professionally is by making the head of sales happy with plenty of order flow through the trading desks.

Of course, if one of the big, important clients followed the analyst’s advice and lost money in an investment, the poor recommendation would negatively affect the analyst’s career. However, the sad fact is that the big, important clients couldn’t care less what the sell-side analyst thinks.

The big important clients have analysts of their own (who of course the clients think are more competent). Clients simply use the sell-side analyst to get access to the company’s management team or to debrief their own analysts about some new technicality of the firm’s business (and perhaps to assess a potential new hire to their firm – the sell-side analyst).

In a phrase, the very structure of the investment business – especially issues related to compensation – is exerting an enormous influence on the recommendations published by the analyst. This is one of the “structural factors” we mentioned in the introduction and which we teach more about in our IOI 101 Course on Behavioral Biases and Structural Factors.

You can see evidence of these structural factors by pointedly reading a sell-side research report and noting that…

- Analyst target prices have a 12-month time horizon. Hedge funds are incentivized on an annual basis, so investment banks’ recommendations are geared to that timeframe. Why should individual investors care about an arbitrary 1-year period at all? This point is especially salient when you realize that most investors’ goals are much further in the future and there is a tax disincentive to realize short-term profits!

- Opinions change more often than business conditions do. Goldman started the year off by upgrading First Solar to a Buy. Not even a full fiscal year has gone by and the analyst has already made a significant change in his published best-case value. Most of the value of a firm is generated by the assumption that it will be a going concern for many years. Unexpected crises or windfalls can suddenly change the long-run fortunes of a firm, but we think the frequent opinion changes are more usually tied to the need for a research analyst to create reasons to transact.

- Opinion changes show changes in target prices that are too extreme. In the case of First Solar, Goldman’s original target price was 50% higher than the level it was trading at the time. The stock has lost 45% during the year, and now the analyst has pulled his target price down to about the current market price. Have the long-term business conditions changed so much that the value of the enterprise is really different by 100%? That is hard to believe!

In addition to these structural factors, behavioral biases – the cognitive quirks that affect human decision-making processes – enter the picture as well.

Analysts are People Too

Goldman’s First Solar recommendation – issued on January 6 of this year when the stock was trading for about $70 per share – saw the stock trading at over $100 per share within 12 months.

During the next ten months, First Solar’s share price fell by about 45% to $40 per share – over $60 lower than the original target price (see our illustration below).

Any time an analyst publishes a target price or a fair value estimate, he or she becomes psychologically anchored to that price. Once anchored, a person is able to minimize and rationalize any information that might prove contrary to the stated opinion. I cannot answer whether the analyst’s original valuation attempt was correct or not (after seeing this downgrade, we’re interested in doing a valuation of First Solar, but haven’t done one yet), but I can guarantee you that he was very focused to his $100 / share anchor of a target price as First Solar’s share price started falling.

Anchoring is a pernicious problem for investors, but there are ways to avoid it and lesson its deleterious effects. We will discuss those in our next article in this series, about valuation methodology.

The market serves as a cruel feedback mechanism for analysts and investors. Analysts spend a great deal of time thinking about short- and long-term strategic factors, digging into the business and the company’s accounts, and talking with people in the industry. At the end of that process, they publicly announce a verdict. The problem is that, past maybe a day or so, the market doesn’t care about anyone’s verdict – whether that anyone is a guy sitting at Goldman’s wood paneled offices in Manhattan or a guy sitting in a modest office in Omaha.

It is difficult to psychologically accept the pain of being publicly wrong, and when it happens long enough, people eventually seek to remove the cognitive dissonance by resorting to a strategy called “herding.” Bovine images are appropriate to this behavioral bias, because as animal behavioralist Temple Grandin knows, as long as cattle are in a herd, they will very happily walk together to the slaughterhouse. Like cattle, security analysts don’t mind being wrong so much as long as they are wrong with everyone else. The market demonstrably thinks that First Solar is worth about $40 / share, so whether that is a proper valuation or not, the analyst feels soothed by agreeing with the market.

The only way to counteract this very strong behavioral bias of herding as it relates to investments is by having a sensible, consistent, provable framework for assessing value and comparing that assessment to the current price of the stock. Assessing stock price in a vacuum devoid of valuation is a recipe for bad decisions.

This article has just touched on some of the structural and behavioral issues at work when a sell-side analyst issues a recommendation change. In our next article, we will look more closely at the valuation method the Goldman analyst used to derive his target price for First Solar. Spoiler Alert: If he were a doctor, he would be in danger of a malpractice suit.

Stay tuned!

This article originally appeared in Forbes.