The harshest critics say that Berkshire Hathaway’s Tech sector investments – Apple and IBM – are like bets on horses whose next stop is the glue factory. The kindest critics say that at the very least, both firms’ best days are behind them.

The critics are wrong. Here are three reasons why.

Both Firms Are Undervalued

We recently published several articles detailing our step-by-step valuations of IBM and of Apple. As long as you accept that the value of a firm is dependent only upon the wealth that the firm can create on behalf of its owners, both these stocks look to be trading for less than what they are worth.

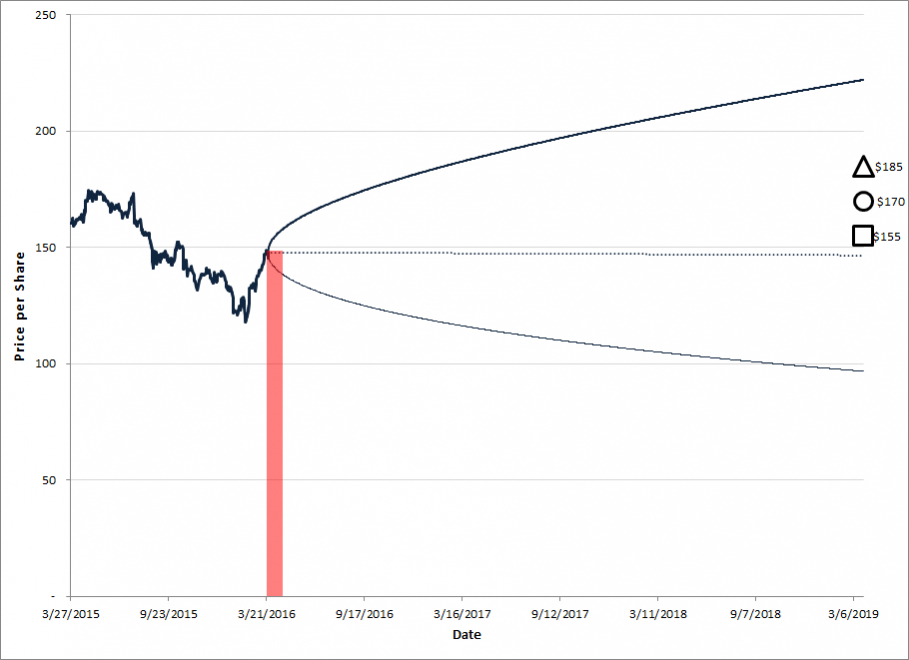

For IBM, we see a fair value range of between $155 / share and $185 / share, and we think the best case is more likely. Feel free to read through this article, which walks through the assumptions in our valuation of IBM.

Figure 1. Source: CBOE, YCharts (data), IOI Analysis. The cone-shaped lines represent the range that the option market sees as the stock’s most likely future price. The triangle on the right represents IOI’s best-case valuation estimate and the square, our worst-case one.

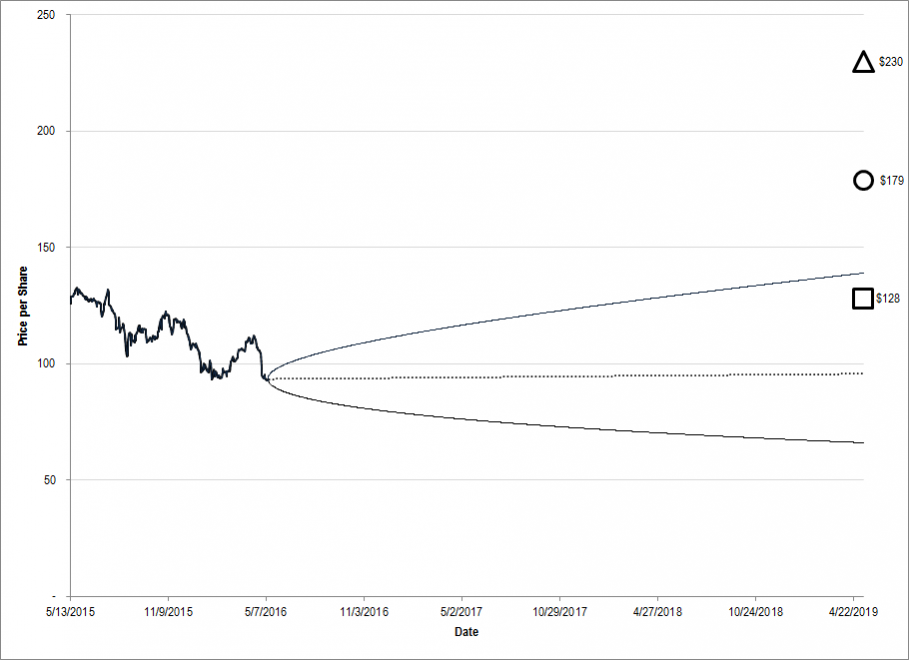

For Apple, we see a fair value range of between $128 / share and $230 / share, and we think the most likely value is around $160 / share. Feel free to read through this article, which shows the detailed assumptions in our valuation of Apple.

Figure 1. Source: CBOE, YCharts, IOI Analysis. The cone-shaped region represents the option market’s best idea for the future price of the stock. The geometric shapes to the right of the diagram represent IOI’s estimated valuation range.

Stock Price Does Not Equal Company Value

Stock prices are some of the most obvious and easily-obtained bits of information about a company. If an investor hasn’t been taught a better way of thinking about investing, they are likely to place too much importance on stock price movement and figure that if a company’s stock price is falling, the company must be failing in some fundamental sense.

So seeing Apple drop heavily after reporting earnings or watching IBM grind its way down from around $200 / share to below $120 / share over a little more than a year offers superficial “proof” that there is something wrong with those companies.

The problem is that the only information that a stock price contains is what price other market participants are willing to buy or sell the stock for at that time. It is, in other words, a measure of other investors’ sentiment and behavior, not a measure of the value of the company underlying the stock price.

My colleague Joe recently reviewed an academic paper about the behavioral bias of “herding.” One line from this paper stood out to both of us particularly:

“Dependence upon the behavior of others most easily substitutes for rigorous reasoning when knowledge is lacking or irrelevant.”

In other words, when investors are confused about how to make decisions they are likely to look for answers in others’ opinions (in the form of stock price movements, for example). In doing this, they are, in effect turning over their investment decision-making process to a group of total strangers.

Buffett and his portfolio managers at Berkshire Hathaway have a disciplined, well-thought out process for assessing value, so are not content to outsource their investment decisions to mob rule.

A Collections of Anecdotes Does Not Constitute Proof

“IBM is losing market share in the Cloud.”

“Apple has stopped being the leader in smartphone design.”

“IBM is destroying its business and relying only on financial engineering to artificially boost EPS.”

“Apple will never be the same since Steve Jobs died.”

Having worked in the business of investment analysis for a long time, I am still surprised by the extent to which collections of anecdotes like these end up constituting the bulk of published research reports and the arguments used in newsletters, blog postings, and golf course stock pitches.

At the end of the day, an anecdote only matters if it is:

- True

- Quantifiable

- Material to a company’s valuation

No matter how many false, irrelevant, and / or immaterial anecdotes are brought to bear in an argument, or however intuitive those anecdotes may seem at first blush, they still fail to affect the value that a company can create for its owners.

The decision makers at Berkshire know how to filter the “signal” from the “noise” and how to assess the value of a company using a disciplined framework.

The morale of the story is not to feel sorry for Warren Buffett and his team for being behind the time and “not getting Tech.” They understand value just fine and their investments in the Tech sector reflect that understanding.