Recently, we have featured some option selling ideas and also some bearish investment structures in our work. This has brought up the topic of “shorting,” so we thought a quick explainer article was in order.

People talk about “shorting stock,” “shorting oil,” and “shorting options,” but the process is very different for each one, as are the financial implications. Even experienced investors may not be fully versed. They will be after reading this article.

Shorting Stocks

Let’s start our discussion of shorting stocks with a discussion of what it means to “go long” a stock – in other words, to buy a stock in the hope that it will increase in price.

An investor who buys a stock does two things:

- Accepts the risk that the company may not be an economic success, and

- Stands to gain in case the company succeeds.

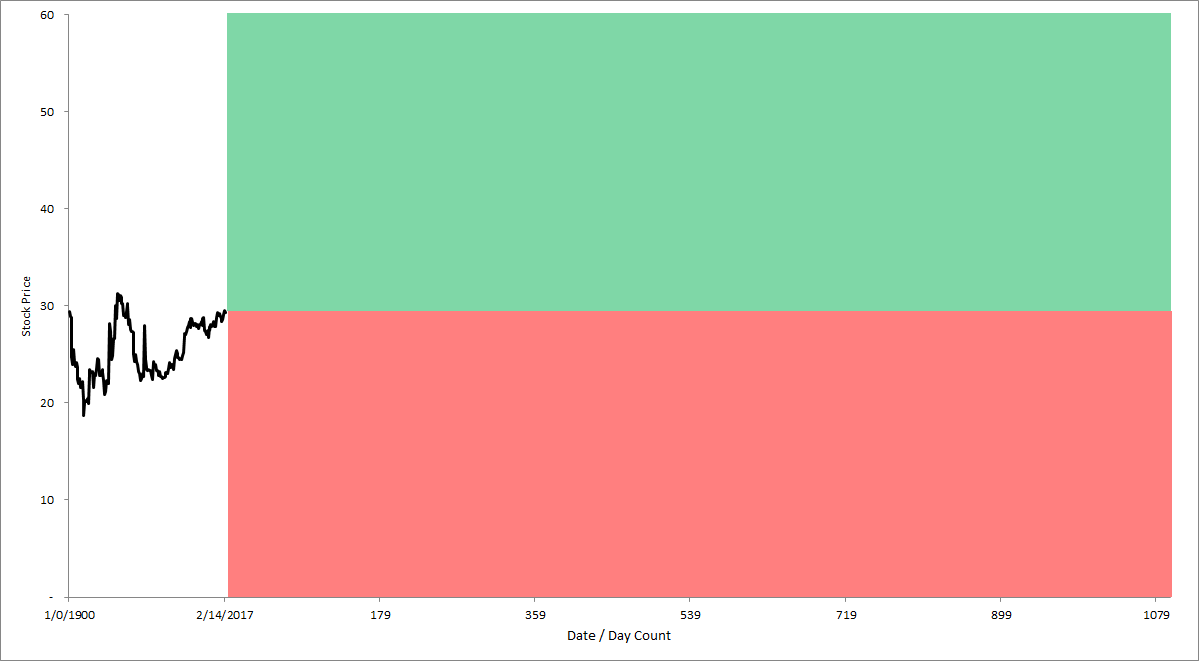

In our way of representing “ranges of exposure,” we would illustrate a long stock position this way:

Figure 1. IOI representation of a “long stock” position. If the stock price rises into the green range of exposure, the investor stands to gain. In contrast, the investor must accept the risk of loss if the stock price falls into the red range of exposure.

An investor who shorts a stock (a/k/a “short-selling”) is just taking the opposite stance from a long investor:

- Accepts the risk that the company may be an economic success, and

- Stands to gain in case the company fails.

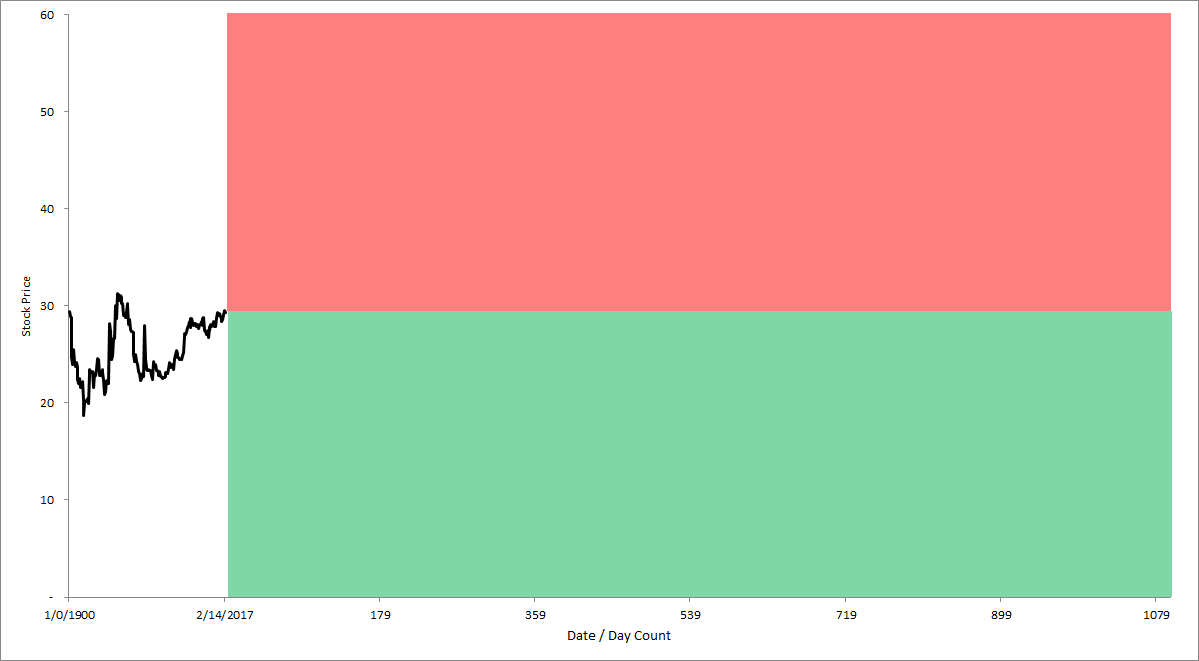

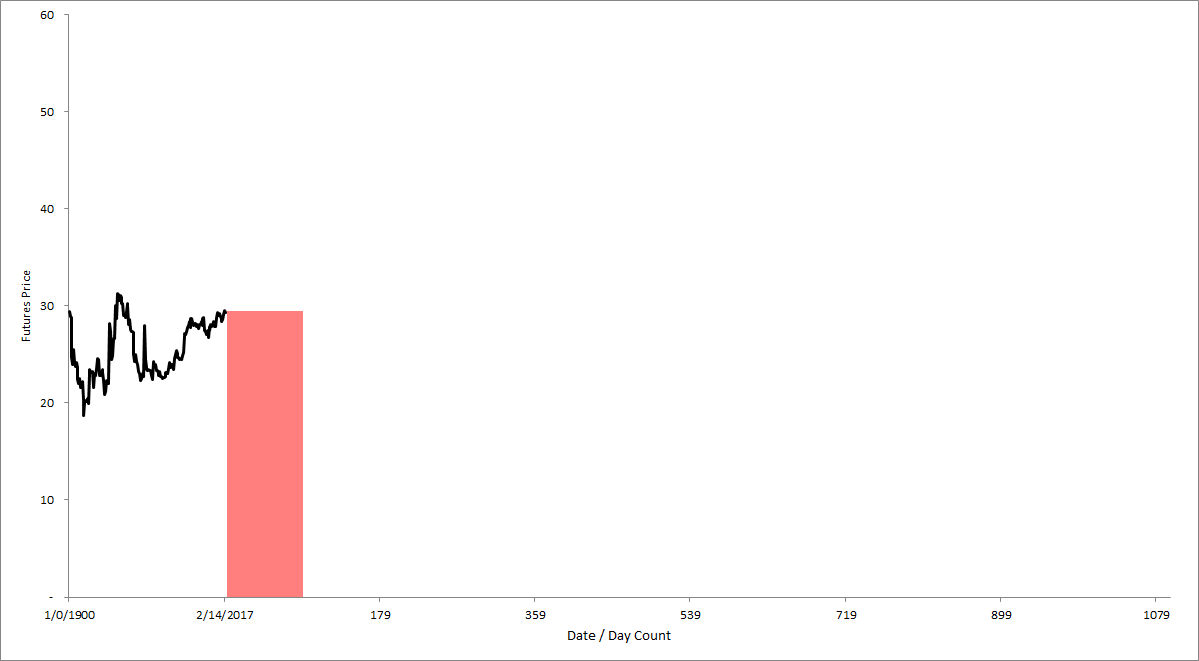

Using our ranges of exposure conventions, here is how we represent a short stock position.

Figure 2. IOI representation of a “short stock” position. Notice that, in this diagram, the investor is accepting the risk of loss if the stock rises and stands to gain if the stock falls.

Looked at in this way, short-selling is easy enough to understand, but the logistics of a short sale are a bit more involved. A short seller must sell shares that he or she does not own. These shares cannot be created out of thin air, but must be among the publicly available inventory.

To sell shares short, the investor must first borrow the shares from an investor who owns them. After borrowing the shares, the short-seller simply sells the other investor’s shares in the open market. The short seller’s plan is to eventually return the shares to the original owner after buying them back in the open market.

The short-selling process in a nutshell

When it is time to return the borrowed shares, if the short seller can buy the shares back at a lower price than that at which he or she sold them, the short seller profits from the difference. If the share price increases, though, the short seller must realize a loss when shares are bought at a higher price than they were originally sold.

The fundamental law of investing is to buy low and sell dear. Being able to borrow stocks allows investors to change the order of buying and selling, but the same law still applies.

Borrowing stocks is such a useful concept that it certainly can’t be free! A short seller who borrows stocks from another investor must pay a “borrow fee” to the investor who owns the shares. The owner of a block of shares can specify to his or her broker that the shares not be lent out – obviously, if you own the shares, you don’t want a short seller pushing down the stock price.

Companies whose shares are heavily shorted will have higher borrow fees than those that have a low “short interest” – this is simple economics: something in great demand will demand a great price.

In addition, a short seller must make sure that any dividends paid on the stock are passed through to the investor from whom the shares were borrowed. As we saw in our recent analysis of Garmin (GRMN), a high dividend yield is one way that a management team can discourage short-sellers from targeting their company’s shares.

All this borrowing, dividend passing, and fee paying requires a lot of bookkeeping. Investment banks have operations groups dedicated to handling the logistics of “stock loans.” Also, one of the most consistent profit centers for investment banks are the “prime brokerage” divisions, business units that serve as the liaisons to hedge funds’ operations and risk control groups, whose tasks often involve facilitating stock loans.

The biggest investment banks generate good revenues and profits from their prime brokerage operations.

Prime brokerage is an important business for investment banks, but also a risky one because they are lending out stocks. What happens if a hedge fund sells a stock short and the next day, the company receives a buyout offer at a significantly higher price (this occurred recently with the US bedding company Mattress Firm). The hedge fund may not have the financial wherewithal to pay for the shares at the higher price, which means that the investment bank would be on the hook to the real owner of the stock!

To protect from this, banks require that short-sellers post collateral or security collateral in a “margin account.” The short-seller will have to post collateral when he or she originally opens the short position (called “initial margin”), and will have to post more collateral if the stock price rises (called “variance margin” or “maintenance margin”).

Shorting Futures

Futures contracts are a form of financial instrument that allows an investor to buy or sell some underlying good. Most futures contracts’ underlying assets are commodities such as oil, copper, Treasury bond rates, orange juice, etc.

Single-name stock futures have been listed for years, but big investment banks have tried their hardest to suppress the use of them because if hedge funds switched to single-name stock future from shorting stocks, investment banks’ prime brokerage businesses would crater.

Unlike stocks, which represent an actual ownership stake in a company, futures contracts are legal promises to buy or sell an underlying asset.

The upshot of this difference is that in order to short sell a stock, an investor has to borrow the stock from someone else first, but to short a futures contract, all an investor has to do is to agree to sell a commodity at a given price at some future time.

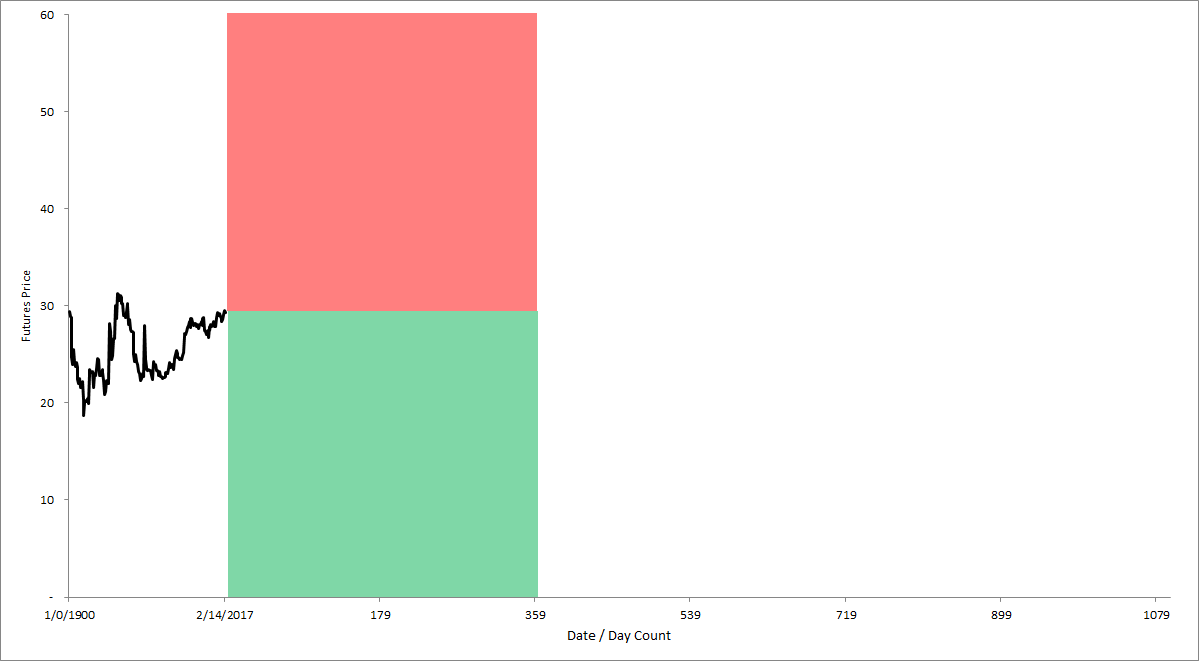

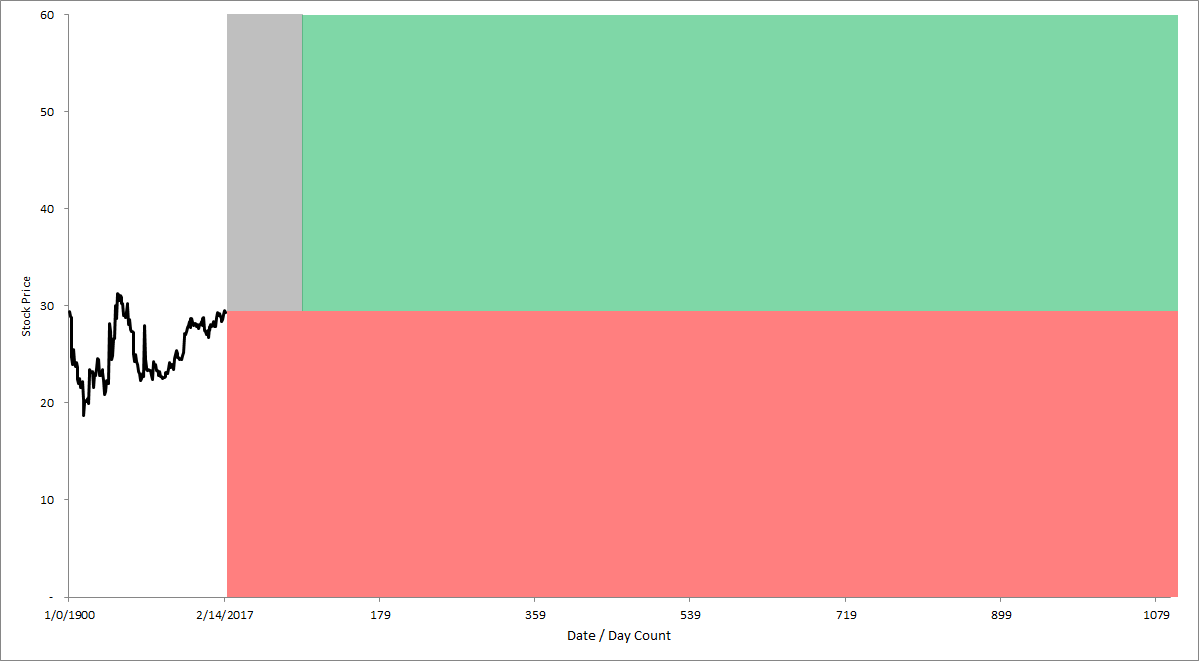

Figure 3. IOI representation of a “short futures” position. Futures contracts have a pre-determined expiration date, which is why our ranges of exposure do not extend to the edge of the diagram as they did for stocks – which are “perpetual” instruments. Notice that for stocks and futures, in order to gain exposure to one range, an investor must simultaneously accept the risk of a price move into the other range.

In other words, a futures contract can be created “out of thin air” and sold, so the laborious process of finding inventory, borrowing it, and selling that in the open market a-la stocks can be avoided. All you have to do is say:

“Sell 30 April at 142!”

As Dan Aykroyd’s character did in the 1980s movie Trading Places.

Both selling or buying futures contracts requires an investor to post collateral in a margin account and to keep paying maintenance margin if the trade goes against them.

Dan Aykroyd’s character is feeling good after successfully shorting orange juice futures.

The fact that an investor can buy a very large “notional value” of some commodity using only a small amount of initial margin is the fact that makes futures a levered instrument. Leverage arises from borrowing money, and someone who buys or sells a futures contract essentially borrows most of the value of the underlying commodity to transact in a relatively large amount of the commodity’s value.

Shorting Options

The IOI 103 class goes into detail about “shorting” options, so I’ll just hit a few high points here.

The big difference between shorting options and shorting stocks or futures is that, whereas shorting stocks or futures always represents a bearish investment, shorting options can express a bullish opinion as well.

At IOI, we prefer to think of “shorting” options as “accepting risk.”

Because options are so flexible, you can either accept risk that a stock will go up (which is a bearish strategy):

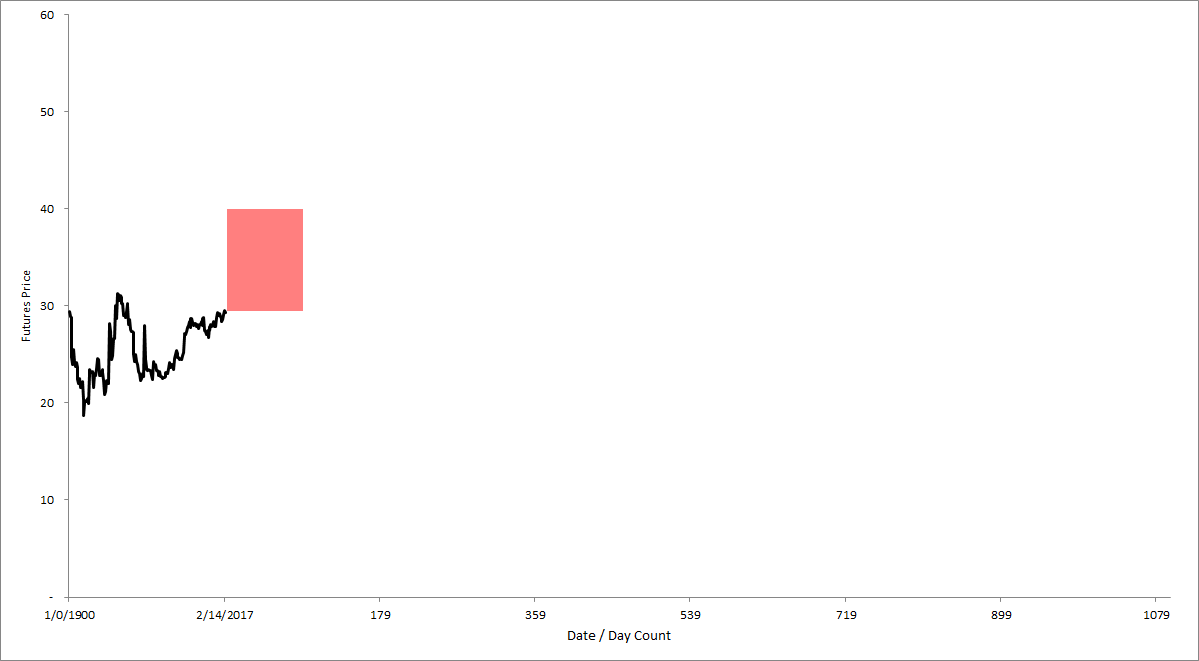

Figure 4. IOI representation of a “short call spread” transaction. In this diagram, we have sold a call option struck “At-the-Money” (i.e., at the present price of the instrument) and bought a call option struck at $40. The total risk we are accepting by this strategy is the $10 difference between the $40 strike and the $30 one. Options are also contracts with definite economic lives.

Or that a stock will go down (which is a bullish strategy):

Figure 5. IOI representation of a “short put” strategy. Here, we are accepting the risk that the instrument’s price will decline below $30. Note that our range of exposures for this figure and for the one above are short. We explain why it is usually better to sell short-tenor options in our IOI 103 course on option mechanics and investment structuring.

Like futures contracts, options represent a legal agreement with some action on an underlying asset as the subject.

Accepting the risk that a stock price might decrease (as shown in figure 5 above) equates to a promise to buy that stock at a certain price (the strike price of the option). In return for making that promise, the buyer of the option pays the seller a monetary “premium,” which reduces the price at which the option seller may ultimately make good on his or her promise and buy the stock. For this reason, we term the strike price minus the premium amount the “effective buy price” of the stock. Our goal as intelligent investors is to make sure we are happy buying the stock at the effective buy price!

Accepting the risk that a stock price might increase (as shown in figure 4 above) equates to a promise to sell that stock at the strike price. In essence, selling a call option is equivalent to promising to short-sell a stock if you do not hold any inventory of the stock. If you do hold inventory of the stock when you sell a call option, your inventory serves as your collateral for the sold call, so your call is completely covered for collateral – this is the origin of the term “covered call.”

Figure 6. IOI representation of a “covered call” investment. Here, the investor holds the stock, but temporarily sells away the upside potential of those shares in order to generate a cash inflow.

Like futures or stocks, a short option position must be collateralized – usually with the amount of risk you are accepting on a given transaction. For example, if you sell a put option on a $20 stock – hereby accepting the risk of a stock price decline – you will have to keep $20 per share in your margin account to collateralize your potential obligation.

Because most option brokers require their clients to fully collateralize any range of risk they are accepting, shorting options is usually a strategy with no leverage. Contrast this with shorting stocks and futures, which are usually strategies with a great deal of leverage.

In a very real sense, as long as you have a clear sense of the value of the underlying asset, shorting options is a safer strategy than shorting other instruments due to the lack of leverage.